|

|

Our consideration of the opera Die Zauberfl�te (The Magic Flute) explores critiques of its libretto, an outline of its structure, the interplay of its two creators, the sources of the libretto, its magnificent music, the influence of Freemasonry, its premiere and success, its universality, an afterthought had Mozart lived longer, early recordings of arias, some key complete recordings, and some sources for further information.

|

|

Few opera librettos could ever pass for great literature. Perhaps the most reviled one of all is Die Zauberfl�te (The Magic Flute). Yet it remains one of the most acclaimed operas of all – proof, perhaps, of the dominance of operatic music over words.

From the very outset, commentators have had a virtual field day trashing the tale of Zauberfl�te, especially in contrast to its universally acclaimed music. One of the few contemporaneous reviews railed: "This ridiculous, senseless and stale product, faced with which understanding must stand still and criticism blush, would but for the composition of the great Mozart be forgotten and scorned. � [P]eople disregarded the nonsense � as they gave themselves over entirely to the delightful melodies � regretting only that such great talents had not been put to a more worthy and nobler subject." From the very outset, commentators have had a virtual field day trashing the tale of Zauberfl�te, especially in contrast to its universally acclaimed music. One of the few contemporaneous reviews railed: "This ridiculous, senseless and stale product, faced with which understanding must stand still and criticism blush, would but for the composition of the great Mozart be forgotten and scorned. � [P]eople disregarded the nonsense � as they gave themselves over entirely to the delightful melodies � regretting only that such great talents had not been put to a more worthy and nobler subject."

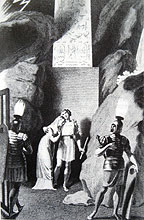

The opening scene

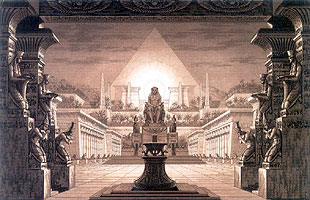

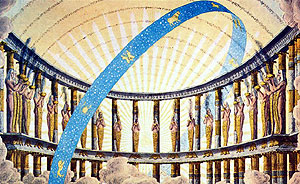

1815 Stage Design by Karl Friedrich Schinkel |

The London Times, reviewing an 1851 Covent Garden revival, agreed: "What is feeble or trivial we readily lay to the stupidity of � the libretto, while that which is great and beautiful springs exclusively from the musical genius of the composer." Wagner (who knew a few things about incredible but engaging sagas) opined: "Here that which is eternal is so irretrievably bound to the veritably trivial tendency of the play." And John Ruskin (in 1861): Mozart "used the greatest power which � the Father of spirits ever yet breathed into the clay of this world � to fit with perfect sound � the foolishest and most monstrous of conceivable human words and subject of thought � . No such spectacle of unconscious � moral degradation of the highest faculty to the lowest purpose can be found in history." More recently, Milton Cross (1953) dismissed it as "made up of so much confusion and nonsense," while Harold Schonberg (1970) called it: " � as na�ve and awkward a pageant as ever disgraced the operatic stage. � No matter what is read into it, the libretto is silly and inconsistent." Only barely mitigating the slight, Edward Dent offered a backhanded excuse: "one of the most absurd specimens of that form of literature in which absurdity is regarded as a matter of course."

Yet the libretto had its defenders, albeit not nearly as many as its detractors. William Mann called it "trivial on the surface but essentially sublime." The eminent Mozart scholar Alfred Einstein asserted that the weakness of the libretto lay only in its diction and insisted that "in the dramaturgic sense" the work is "masterly" and a "piece for all mankind" and that it "is at once childlike and godlike, filled at the same time with the utmost simplicity and the greatest mastery. � Zauberfl�te is one of those pieces that can enchant a child at the same time that it moves the most worldly of men to tears and transports the wisest." He admonished that "one's judgment of the libretto of Zauberfl�te is a criterion of one's dramatic, or rather dramatico-musical, understanding."

In a similar vein, Goethe stated: "More knowledge is required to understand the value of this libretto than to mock it." In a similar vein, Goethe stated: "More knowledge is required to understand the value of this libretto than to mock it."

Schinkel stage design – the Queen |

In the more ascerbic view of Bernard Shaw: "If you don't know Zauberfl�te � then you are an ignoramus." So here's a brief synopsis. A singspiel, its format alternates sung and spoken passages. The musical numbers comprise an overture and two acts. The rest [indicated by brackets] is dialog.

- Act I Introduction: "Au Hilfe!" ("Oh help me!") – The prince Tamino faints, fleeing from a serpent that is killed by Three Ladies of the Queen, who playfully compete for the honor of guarding him.

- Aria: "Der Vogelf�nger bin ich ja" ("I am the bird-catcher") – Amid phrases on his rustic pipes, the Queen's bird-catcher Papageno describes his rustic life and wishes he were equally adept at snaring a mate. [The Ladies seal his lips for boastfully lying that he killed the serpent. They hand the revived Tamino a locket with a portrait of the Queen's daughter Pamina.]

- Aria: "Dies Bildnis ist bezaubernd sch�n" ("This picture is enchanting fair") – Tamino falls in love with Pamina's image. [The Ladies enlist Tamino to rescue Pamina, who has been kidnapped.]

- Aria: "O zittre nicht" ("Oh do not tremble") – In her chamber, the Queen promises Pamina to Tamino if he can rescue her.

- Quintett: "Hm! Hm! Hm!" – Papageno begs for release and agrees to accompany Tamino. The Ladies give Tamino a magic flute and Papageno a set of chimes. [In a splendid Egyptian room Pamina is threatened by Monostatos, the overseer of Sarastro.]

- Terzetto: "De feines T�ubchen" ("My pretty little dove") – Pamina is fettered and faints. [His appearance having scared off Monostatos, Papageno explains his and Tamino's mission.]

- Duett: "Bei M�nnern, welche Liebe f�hlen" ("All men who can feel love") – Pamina and Papageno sing about the wonders of love.

- Act One Finale – Three Boys lead Tamino into a grove with three temples. Voices warn him away from the temples of nature and reason. A Priest (also known as the Speaker) emerges from the temple of wisdom and explains that the Queen is evil, and that their ruler, Sarastro, abducted Pamina to protect her.

Schinkel stage design – the Three Temple Doors |

Tamino plays his magic flute to summon Pamina but instead charms wild animals. Hearing Papageno's pipes he rushes off. Papageno and Pamina are captured by Monostatos's forces but escape when Papageno's magic chimes render them helpless. Sarastro enters with his court, punishes Monostatos for his lust, promises eventual freedom to Pamina, and leads Tamino and Papageno into the temple to face the trials of initiation.

- Act II Introduction: March of the Priests – The priests enter a palm grove. [The priests assent to Tamino undergoing their initiation trials.]

- Aria: "O Isis und Osiris" – Sarastro prays for divine guidance. [Tamino pledges to face the challenges. Papageno agrees only when promised a suitable mate. Both are sworn to silence.]

- Duet: "Bewaret euch vor Weibert�cken" ("Beware the wiles of women") – Two priests deliver a sexist warning.

- Quintet: "Wie? Ihr an diesem Schreckensort?" ("Why? You in this terrible place?") – Tamino remains steadfast against the Three Ladies' temptations but Papageno chatters.

- Aria: "Alles f�hlt der Liebe Freuden" ("All may feel the joys of love") – Monostatos lusts over the sleeping Pamina. [The Queen chases him away and gives Pamina a dagger with which to kill Sarastro so her power will be restored.]

- Aria: "Der H�lle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen" ("The revenge of hell boils in my heart") – The Queen vows revenge. [She departs. Monostatos creeps back in but is repelled by Sarastro.]

- Aria: "In diesen heil' gen Hallen" ("Within these holy bounds") – Sarastro proclaims that love will triumph over revenge. [Papageno, thirsting, is given water by an old woman who claims to be his sweetheart.]

Schinkel stage design – the Trials of Water and Fire |

- Trio: "Seid uns zum zweitenmal willkommen" ("Be welcome once again to us") – The Three Boys bring food and the magic flute and chimes. [Unaware of the vow of silence, Pamina is chagrined that Tamino won't talk to her.]

- Aria: "Ach, ich f�hls, es ist verschwunden" ("Ah, I feel it now has vanished") – Pamina grieves that Tamino has abandoned her and longs for death.

- Chorus: "O Isis und Osiris, welche Wonne!" ("O Isis and Osiris, what feelings of joy") – The priests hail Tamino's coming life of brightness and purity.

- Trio: "Sol lich dich, Teurer, nicht mehr she'n?" ("Shall we, my dearest, not meet again?") – Sarastro explains that Tamino and Pamina will be united after he faces his final two trials.

- Aria: "Ein M�dchen oder Weibchen w�nscht Papageno sich" ("A maiden or little wife would Papageno like") – Papageno pines for a suitable companion. [The old woman pities him. When he reluctantly agrees to be faithful to her she is transformed into a lovely young woman – his intended mate, Papagena – but is whisked away by the Speaker, as Papageno is not yet worthy of her.]

- Act II Finale, comprising separate but continuous numbers:

- Quartet: "Bald prangt" ("Soon") – The Three Boys prevent Pamina from stabbing herself and assure her of Tamino's love.

- Trio: "Der, welcher wandert diese Strase voll Beschwerden" ("He who travels this path with burdens") – Two Armed Men guarding the temple gate fortify Tamino to meet Pamina.

Schinkel stage design – Inside the Temple |

- Duet and March: "Tamino mein! O Welch ein Gl�ck!" ("My Tamino! Oh, what happiness!") – Hailing the powers of the magic flute, Pamina's love guides Tamino through the final two trials of fire and water.

- Aria: "Papagena!" – Unable to find Papagena, Papageno prepares to hang himself. The Three Boys rush in to implore him to summon Papagena with his chimes.

- Duet: "Pa pa pa" – Stuttering with delight, Papageno and Papagena extol their simple future together.

- Quintetto: "Nur stille, stille!" ("Now quiet, quiet!") – The Queen, Monastatos and her Three Ladies invade the temple but Sarastro breaks their power and plunges them into eternal night.

- Chorus: "Heil sei euch Geweihten" "Hail to thee, Initiates") – The populace hails Tamino and Pamina, robed as initiates, and extols the victory of eternal wisdom.

The libretto was by Emanuel Schikaneder (1751 - 1812), a versatile actor of roles from Shakespeare to farce and a sometime impresario who had mounted Mozart's prior singspiel, Die Entf�hrung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio), with great success in 1783. Known for the splendor and ingenuity of his productions, in 1789 Schikaneder took over the directorship of the Freyhaus, a huge boxy theater in the Vienna suburbs that boasted a deep stage and a capacity of 1,000, where he installed a large (for its time) orchestra of 35 and hired a regular cast of fine singers. The libretto was by Emanuel Schikaneder (1751 - 1812), a versatile actor of roles from Shakespeare to farce and a sometime impresario who had mounted Mozart's prior singspiel, Die Entf�hrung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the Seraglio), with great success in 1783. Known for the splendor and ingenuity of his productions, in 1789 Schikaneder took over the directorship of the Freyhaus, a huge boxy theater in the Vienna suburbs that boasted a deep stage and a capacity of 1,000, where he installed a large (for its time) orchestra of 35 and hired a regular cast of fine singers.

Schikaneder and Mozart |

His popular productions specialized in parodies, satires and fantasies, using imposing sets, ornate props and spectacular stagecraft. He authored most of them, but also attracted the talents of Schiller, Goethe and other notable playwrights.

How did Schikaneder manage to enlist Mozart? A common myth is that the composer was destitute and would stoop to any project that promised money. As recapped by H. C. Robbins Landon, his modest income went to pay off old debts and could not support the opulent clothing, coiffed hair and general standard of living required to mix with nobility upon whose commissions he depended; public concerts were rare; publishers paid a relative pittance for his works (which in any event were widely pirated with impunity); court commissions dried up after Lorenzo da Ponte, the librettist with whom he had worked on his last three Italian operas (Le nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni and Cos� fan Tutte), was dismissed from his post in a scandal; and so by early 1791 Mozart was reduced to writing dance music for society balls and novelty pieces for mechanical clocks and glass harmonicas. Yet, Mozart considered himself a German musician and was eager for an opportunity to write another quintessentially German opera as a bulwark against the dominance of florid Italian and frivolous French imports. Moreover, although perhaps not to the extent depicted in Amadeus, he enjoyed popular theatre, and Schikaneder was keen for another oriental fantasy.

Little is known about the composition of Zauberfl�te and the interplay of its creators. Although Mozart's autograph score contains no dialog, based upon the superiority of the dramaturgy to those of Schikaneder's sole authorship (including many spinoffs of Zauberfl�te) David Cairns considers the libretto to have been a joint effort. (Schikaneder's stage manager later would claim – but only after Schikaneder's death – to have written it all by himself.) Branscombe suggests that Mozart began writing in mid-April 1791 during a lull in his productivity, and Nicholas John notes that composition was interrupted by La clemenza di Tito (The Clemency of Titus), a lucrative commission for which Mozart travelled to Prague, and the Requiem, which he would leave incomplete. Mozart entered the overture and the priests' march in his thematic catalog the very day before the premiere, but John notes that he typically saved the overtures to his operas for last and speculates that he wrote the march to facilitate the staging.

Joseph Campbell traces the basic plot of Zauberfl�te to the universal structure of initiation myths and rituals from all over the world in which a hero typically is lost in a dark forest or wild place, is called to adventure, at first refuses the call, is offered supernatural aid, meets a guardian at a threshold who presents challenges, enters into the underworld, confronts a father-figure who initially appears to be an ogre, undertakes a supreme journey or test and finally is rewarded with admittance into the highest level of society. Joseph Campbell traces the basic plot of Zauberfl�te to the universal structure of initiation myths and rituals from all over the world in which a hero typically is lost in a dark forest or wild place, is called to adventure, at first refuses the call, is offered supernatural aid, meets a guardian at a threshold who presents challenges, enters into the underworld, confronts a father-figure who initially appears to be an ogre, undertakes a supreme journey or test and finally is rewarded with admittance into the highest level of society.

Sarastro, from an 1826 paperback |

On a basic symbolic level, the plot can be seen as a journey through life, with Tamino/Pamina (who sublimate their desires in favor of intellect and propriety) and Papageno/Papagena (who content themselves with earthy simplicity) representing the extremes of humanity, as do Sarastro and the priests (morality and social order) and the Queen and Monostatos (evil and chaos). In an exceptionally detailed analysis of the libretto (with barely a word about the music) Nicholas Till traces the strands of its underlying symbolism to the Cabbala (numerology), Zoroastrianism (the metaphysical struggle between dark and light), Gnosticism (Papageno's earthiness), the Rosicrucians (mysticism and the passage to redemption), and the Enlightenment (its conviction that civilization depends upon the rule of the elite to preserve our permanent spiritual values).

Commentators also have ascribed the specific elements of the plot to disparate sources. Thus, Branscombe traces the opening scene to an 1177 tale by Cr�tien de Troye, the invocation of Egyptian gods and rituals to the Abb� Jean Terrason's 1731 Sethos (which included armed men, three ladies and the hero's purification through trials of fire and water, as well as much of the text of the "O Isis und Osiris" aria), and a hero falling in love with a portrait, three boys who give wise advice and a slave who spies on the heroine to popular fairy tales. Contrasting couples and the birdman were popular characters in Baroque and lowbrow Viennese theatres and a dejected lover's half-hearted threat to hang himself a staple of commedia dell'arte. Other elements were derived from Dschinnistan, a 1786 collection of oriental fantasies by Christoph Martin Wieland that added to the Sethos elements a temple of friendship and benevolence, a lustful black slave and a hero with a magic flute. Dschinnistan, in turn, generated a derivative story by Jakob August Liebeskind with a noteworthy title: "Lulu, oder der Zauberfl�te" ("Lulu, or the Magic Flute"). Operas, too, provided precedent. William Mann points to Osiris, a 1781 opera by Johann Gottlieb Naumann in which the hero is united with a kidnapped princess in the Temple of the Sun, and Der Stein der Weissen ("The Philosopher's Stone"), a 1790 magic opera pastiche to which Mozart had contributed a brief segment and which featured noble and comic pairs of lovers, good and bad genies and trials of fire and water.

Most often cited as precedent is Wenzel M�ller's opera Kaspar der Faggonist, oder Die Zauberzither ("Kaspar the Bassoon Player, or the Magic Zither"),

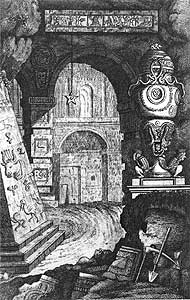

The fire and water trials |

produced at a rival theatre in July 1791, complete with a hunting prince and his comic servant who must evade dangers to save the daughter of a fairy kidnapped and held in a castle by a malevolent wizard – and lots of magic instruments. Mozart is known to have seen it. Given the seemingly abrupt change in the Zauberfl�te plot in the Act I finale (in which the Queen and Sarastro appear to exchange roles) many early analysts suspected that the libretto was revised in mid-course in response to Kaspar in order to avoid charges of plagiarism. As the ostensibly authoritative 1908 Groves Dictionary of Music and Musicians put it: "Just as it was ready, [Schikaneder] found that the same subject had been adapted by [M�ller]. He therefore remodeled his materials." That theory has been widely discredited. For one, it presupposes that both play and score were written in linear order from start to finish, a chronology belied by Alan Tyson's research that identified portions of the autograph written on eleven different types of paper. Mozart included snippets of his score when writing to his wife (who was at a distant health spa) in June, suggesting that the entire work was already well underway before the first presentation of Kaspar. (He also reported to her that: "there is nothing in [Kaspar] at all," although that could have been defensive.) In any event, Rodney Mills points out that copying at the time was widespread and accepted, and so even a strong resemblance with Kaspar was unlikely to have motivated radical revisions in a project already in progress.

Cairns presents a more modern view – that there is no change in the plot at all, since all the time we are seeing the Queen through Tamino's eyes. Thus Tamino first believes his rescuers (the Three Ladies, who serve the Queen) and, perhaps heightened by his passion for her lovely daughter, assumes that she is benevolent but only later is enlightened by the morally superior Sarastro who reveals her true nature. Robert Donington views the evolution in the Queen's role in Freudian terms – Tamino first clings to her as a mother-figure but then grows away from her as he matures. Sandra Corse goes further, noting that meaning often arises from the resolution of opposites and questioning the very notion that a work of art needs to be unified at all. On that basis, if the libretto strikes us as confusing or irrational, perhaps it reflects the complexity of the human condition better than a plot that proceeds with logic to full resolution of its inherent conflicts.

Regardless of their views of the libretto, nearly all critics praise Mozart's music as raising the clich�d situations and characters to sublime levels. Julian Rushton hails "the music, hanging like a series of mixed jewels upon the brittle threads of the plot, illuminating the situations, deepening the pasteboard characterization and gathering, in two immense finales, all the dramatic threads into a labyrinthine musical organization." Mann credits Mozart with binding together the libretto through "the abundant humanity he found rooted in every scene and character" and "pouring out his ripest genius on it all." Paul Henry Lang acclaims Mozart as "the greatest musico-dramatic genius of all time" whose temperament approached everything in terms of the language of music and thereby deepens it with symbolic overtones. Specifically, in Zauberfl�te, "this amalgamation of all musical civilizations, Mozart united � all the symbols of human dreams and desires." Regardless of their views of the libretto, nearly all critics praise Mozart's music as raising the clich�d situations and characters to sublime levels. Julian Rushton hails "the music, hanging like a series of mixed jewels upon the brittle threads of the plot, illuminating the situations, deepening the pasteboard characterization and gathering, in two immense finales, all the dramatic threads into a labyrinthine musical organization." Mann credits Mozart with binding together the libretto through "the abundant humanity he found rooted in every scene and character" and "pouring out his ripest genius on it all." Paul Henry Lang acclaims Mozart as "the greatest musico-dramatic genius of all time" whose temperament approached everything in terms of the language of music and thereby deepens it with symbolic overtones. Specifically, in Zauberfl�te, "this amalgamation of all musical civilizations, Mozart united � all the symbols of human dreams and desires."

THE FIRST THREE ARIAS

Papageno's "Folk" Song:

Tamino's Romantic "Portrait" Aria:

The Queen's Opera Seria Coloratura:

|

Till agrees, crediting Mozart with deep knowledge of the philosophical trends of his time and a profound understanding, akin to Shakespeare, of human spiritual and social needs. Einstein finds it notable that no two portraits of Mozart are similar and no remains are known, "as though the spirit-world wished to show that here is pure sound � triumphant over all chaotic earthliness."

Many analysts hail the wide variety of divergent musical forms and orchestration that Mozart used, each in a suitable way to enhance character and situation. Thus, Charles Osborne describes the first several numbers as lyrical comedy (the Ladies' trio, as they engage in a mock-battle over the sleeping Tamino), a folk song (Papageno's air, as he revels in his simple desires), a romantic aria (Tamino enraptured by the portrait of Pamina) and opera seria (the Queen's coloratura). Later we encounter chorales to depict the priests' religious devotion, formal counterpoint to simultaneously present characters' divergent emotions, dances to mock Monostatos' militia disarmed by Papageno's magical instrument and, of course, a triumphant chorus at the very end. Commentators note that much of this was facilitated by the inherently discontinuous nature of the singspiel format, in which dialog separates the musical numbers so they can be a mix of heterogeneous elements without fear of seeming to clash or lacking cohesion. Also significant is the genre's roots in folk tales and vernacular which averts the need to respect the formality of classical structures and afforded Mozart the freedom to sidestep the demands of established operatic formulae.

Critics further praise the deliberate simplification of the music. Cairns rejects the once prevalent view of Zauberfl�te as a reversion to primitive drama (and thus a squandering of Mozart's talents), but rather views it as a purposeful distillation of direct melodies, pure harmonies and luminous textures. Indeed, not only the dialogue but even the arias proceed mostly in efficient, linear fashion, dispensing with the repetitious padding in Mozart's prior Italian operas. After all, careful editing, restraint and refinement in art is harder to achieve – and far more impressive – than unrestrained abandon. On one level, the musical numbers fit their characters and situations brilliantly. Thus Papageno's introductory aria (# 2 in our outline) is rustic, effortless and charmingly na�ve, followed by Tamino's limpid, elegant outpouring of sincere emotion (# 3) and the Queen's venom (# 4). So does the instrumentation, as Mozart invests the accompaniments with a wide variety of timbres, all carefully tailored to the dramatic function. On a more intuitive level, Mozart uses motivic repetition and his choice of keys to identify and to form logical links among characters and situations. Thus Einstein assigns F major to the priests and their world, C minor to sinister powers, G major to buffoon elements and E-flat major with the humanitarian ideals of the opera.

Yet subtlety abounds as well. Monostatos sings hastily and is accompanied by nervous figures to undercut his cunning, the tense vocal leaps of the Queen's first aria suggest her cold contrivance well before we first are led to suspect it,

The Entrance of the Evil Forces:

Conflict Between Music and Words:

|

and the unassuming flute that accompanies the supposedly terrifying fire and water trials can be heard as calm, moral purity in the face of mortal danger. Or consider the penultimate number, "Nur stille, stille!" in which the evil Queen, her Three Ladies and Monostatos invade the temple – its sheer melody is so catchy, buoyant and ingenuous that their evil plot can't possibly be taken as a viable menace. On a yet deeper level, Branscombe notes that the musical inflections often abrade the text. As one of many examples, he cites the very first line in which Tamino cries out: "Zu Hilfe! Zu Hilfe! Sonst bin ich verloren! ("Help! Help! Or I am lost") – although the spoken accent would fall on the final word, Mozart places it on the relatively inconsequential "bin," which distorts the literary sense but sounds forceful at the apex of an insistent rising and falling musical phrase, thus documenting to Branscombe that Mozart valued emotion above the actual words. The anonymous Covent Garden reviewer went even further to suggest that, by accompanying Tamino's and Pamina's climactic passage through their final fire and water tests with a wimpy solo flute, Mozart showed his contempt for the triviality of the story.

In retrospect, Mozart's Zauberfl�te music has been hailed for its influential innovations, even beyond its first use of three trombones, a basset horn or a xylophone in an opera score. Eric Smith asserts that, alone among Mozart's work, it contains the seeds of Romanticism by combining folk song, an exotic setting and symbolical meaning and, in the lengthy exchange between Tamino and the Speaker in the first finale, by bridging the prior established rigid classical division between dry recitative and florid melody. To that we might add the sheer sound of Tamino's and Pamina's arias, tenuously poised between classical reserve and stirring emotion that seems ready to burst – Rodney Milnes calls them "rhapsodic outpourings of purely musical eloquence" that adhere to no 18th century form. Indeed, Beethoven proclaimed it Mozart's best opera (largely for including so many perfected musical forms) and a masterpiece of musical logic (for using keys according to their psychological properties) and composed two sets of variations on its aria themes. Wagner acknowledged that Zauberfl�te laid the foundation for his work and regarded it as a masterwork that never would be surpassed. Goethe even was inspired to attempt a sequel (in which Monostatos tries to steal Tamino's and Pamina's baby son). (Even the libretto proved influential – John traces Zauberfl�te's influence through the further development of German opera from Fidelio's triumph of virtuous love leading from the trials of prison to brilliant freedom and Freischutz's test of love and fidelity, to the allegorical dramas of Wagner.)

Perhaps the greatest motivation for Zauberfl�te was Freemasonry. Both Schikaneder and Mozart were wholehearted Masons and may have seized upon Zauberfl�te as an opportunity to communicate their spiritual ideals to a wider audience and perhaps to boost Masonic morale in time of need. Perhaps the greatest motivation for Zauberfl�te was Freemasonry. Both Schikaneder and Mozart were wholehearted Masons and may have seized upon Zauberfl�te as an opportunity to communicate their spiritual ideals to a wider audience and perhaps to boost Masonic morale in time of need.

Masonic symbols – square and compass |

Indeed, they may have viewed Zauberfl�te as an act of rebellion, as Masonry was under dire attack from both Church and state (and in fact would become nearly extinct in a few more years).

Freemasonry began in England around 1700 and flourished in France and Austria. Jacques Chailly notes that it arose in a time of weakened spiritual values and was attractive as a substitute to those who sought spiritual substance but perceived an emptiness in the Church, instead harking back to antiquity as the source of ethics and embracing the values common to all faiths. Organized into lodges with roots in medieval guilds, it attracted free-thinkers in need of hierarchical structure, ceremony and recognition and thus held particular appeal for scientists and artists during the age of Enlightenment and its emphasis on individuality. As the doctrines of Freemasonry were suffused with inspecific religious overtones (as well as the mysteries of antiquity) and prized a secular vision of social ethics, both the Church and civil governments felt threatened and moved to control, limit and repress it. Indeed, in 1775 the Austrian police required members to register and the Emperor forced the Viennese Masons to consolidate into three lodges of no more than 180 members. Mozart joined the "Zur Wohlt�tigkeit" ("Benificence") lodge in December 1784 as an Apprentice and quickly rose in the echelons, being promoted to Journeyman in three weeks and Master (the highest Austrian rank) in three months. The lodge had been founded by Ignaz von Born, who published a study relating Masonic practices and beliefs to those of the ancient Egyptians, and it became a center of intellect and culture. Mozart was a devoted member, writing eight works for specific lodge rites, including his magnificent 1785 Masonic Funeral Music and his last completed work, a Masonic cantata. As summarized by Maynard Solomon, the Masonic ceremonies appealed to Mozart's theatrical impulses, its ancient traditions touched his abstract religious yearnings and its creed fit well with his own personal beliefs, which embraced an elastic approach to religion, self-development, spiritual uplift and humanitarian aspirations; ideals of liberty, equality, tolerance, mutual aid, sacrifice and benevolence; and a vision of salvation through logic and reason.

Nearly all of these spiritual values found their way into the libretto of Zauberfl�te. Most patently, the screening and trials of Tamino closely follow Masonic initiation ritual.

Libretto frontispiece full of Masonic symbols |

Indeed, the frontispiece of the first publication of the libretto was an engraving filled with palpable Masonic (and some Rosicrucian) symbols. Some of the symbolism of the libretto is rather obvious. Thus, Sarastro dwells in the temple of wisdom and leads Tamino (mankind) by mediating between the other two temples of nature and reason (representing the poles of human existence – animal impulse and scientific intellect). Others dwell at a deeper, Freudian, level – Donington interprets Tamino's entry with a bow but no arrows as signifying his incomplete manhood.

In an exhaustive analysis, Chailly goes much further to interpret each plot detail in terms of Masonic beliefs and rituals, most of which surely would escape a typical opera-goer. Thus, he likens Tamino's fainting to the prostration with which initiation begins and the padlock with which the Three Ladies clamp Papageno's lips to the "seal of discretion" that was part of the Masonic initiation ceremony in women's lodges. Even the magic flute itself resonates with figurative meaning by uniting all four ancient elements and thereby symbolizes perfection – it is sounded with the breath (air) and is described by Pamina as having been carved from a tree root (earth) and produced during a downpour (water) amid flashes of lightning (fire) – the same elements that comprise Tamino's trials that, in addition to passage through fire and water, include isolation (earthly burial) and silence (air), all fundamental to the Masonic creed. Cairns further suggests that the flute, a single instrument equivalent to multiple shepherd pipes, reflects the Masonic incorporation of ideas from multiple religions and thus symbolizes the diversity of the opera's music.

The music, too, has been deemed to incorporate Masonic elements. The frequent use of groups of three chords, motifs of three notes and rhythms of three all reflect the primary integer in Masonic numerology.

THE OVERTURE

The opening three "knocks"

The fugue begins:

|

Recurrent tonalities are associated with Masonic music – C major for light, c minor for the threat of death and, above all, E-flat major (three flats). Counterpoint has been held to signify the Masonic ideal of human equality. Indeed, Chailly depicts the overture as a resum� of the action within a Masonic context. Thus, it begins with three chords in the rhythm of knocking to enter a Masonic lodge, then thematic fragments depict groping through chaos, a fugue with no modulation suggests the rigidity (and tedium) of society, repetition of the three chords, each now heard three times, emphasizes the establishment of Masonic order, and then the fugue is heard again, but this time with frequent modulation abounding in minor keys and chromaticism to suggest the richness of life when infused with Masonic ideals, capped by fanfares to celebrate the triumph of Masonic thought.

However, several commentators caution against reading too much Masonic symbolism into Zauberfl�te. In 1876 M. A. Zille, himself a Mason, ascribed the characters to political figures of the time – Tamino to Emperor Joseph II (a tolerant reformer under whose reign Freemasonry flourished), the Queen to Maria Theresa (his repressive forebear who had tried to extinguish the lodges in her realm) and Sarastro to Ignatz von Born (the revered master of Mozart's lodge). (Zille also asserted that Pamina represented the Austrian people, an allusion that seems obscure.) Branscombe notes that such musical elements as counterpoint (suggesting equality), the "Masonic" key of E-flat, the "knocking" rhythms of dotted threes and instrumentation featuring "Masonic" trombones, clarinets and basset horns all were used extensively in Mozart's other non-Masonic late works.

One aspect that has raised many modern eyebrows is the depiction of women. As Christoph Martin Wieland quipped, as far as women were concerned the Masons opened their hearts but not their lodges. Till relates this to the Enlightenment dichotomy of revering and idolizing women in the private domestic sphere while fearing their power and denigrating them in public.

Monostatos and Pamina

Johann Ramberg (1826) |

Thus in Zauberfl�te the wise Sarastro counsels that women must be guided by men, and chief among the initiation ordeals is the need to resist the temptations and perfidy of women, as most glaringly stated in a duet (# 11) of two priests who warn that women's tricks lead to despair and death (and indeed in the following scene it is the Queen's Three Women who tempt Tamino and Papageno to abandon their quest). Yet, Till notes that the duet is set to perfunctory music, as if Mozart disapproved or at least made light of the text (although he didn't excise it altogether, as he did with other original verses that didn't fit his conception). And many commentators note that Pamina not only is found worthy of initiation (albeit because of her personal bravery, deemed atypical for her gender) but leads Tamino through his final trials, and that both emerge for a triumphant joint initiation, as if to suggest that the two genders ultimately deserve equality.

Less equivocal is the text's racism, embodied in the villainous Monostatos, the sole person of color in the entire cast and who is fixated on raping Pamina. Not only is this characterization deeply embedded in the myth of black men's raging sexual desire (and the consequent white fear of miscegenation), but the text makes the source of his evil abundantly clear. Thus in his aria (# 13) he proclaims: "Alles f�hlt der Liebe Freuden, schn�belt, t�ndelt, hertz und k�sst; und ich soll die Liebe meiden, weil ein Schwarzer h�sslich ist. � Weiss is sch�n! Ich muss sie k�ssen; Mond! Verstecke dich dazu!" (Everyone feels love's joys, bills, coos, hugs and kisses, but I must shun love because a black man is ugly. � White is beautiful! � I must kiss her; Moon! Hide yourself from it!") This time, Mozart's peppy setting does nothing to dispel the patent message of the text that such behavior is shameful yet inborn as a matter of race. Modern producers face the unenviable and perhaps insoluble quandary of whether to sanitize this aspect for modern sensibilities or to admit that Mozart was a man of his time and reflected the social assumptions of his age, both progressive and pernicious.

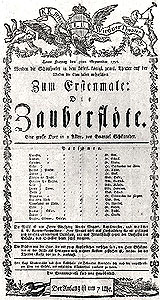

Mozart personally conducted the Zauberfl�te premiere on September 30, 1791 (and the first repetition) from the fortepiano. As would be expected for a typical Schikaneder production, the original libretto was full of specifications for lavish sets (13!), props, stage directions and even sound effects (but, curiously, not costumes). Mozart personally conducted the Zauberfl�te premiere on September 30, 1791 (and the first repetition) from the fortepiano. As would be expected for a typical Schikaneder production, the original libretto was full of specifications for lavish sets (13!), props, stage directions and even sound effects (but, curiously, not costumes).

Schikaneder as Papageno |

The only two reviews published during Mozart's life both praised the staging while mustering less enthusiasm for the work itself. (One called it "an unbelievable farce" and the other cited "the inferiority and diction of the piece.") The principal roles were tailored to suit the members of Schikaneder's stock company – as characterized by Rushton, Mozart's sister-in-law Josepha Hofer, a fiery coloratura, was the Queen; 17-year old Anna Gottlieb (who had sung Barbarina in the premiere of Nozze di Figaro at age 12!) played Pamina with impulsive pathos; Benedikt Schack, a lyrical tenor, was Tamino; Franz Xaver Gerl, known for his fine low notes, was Sarastro; and Schikaneder himself took the role of Papageno (and an engraving of him in costume adorned the libretto). Donald Mitchell suggests that Schikaneder wrote the role to reflect his own character – a combination of buffoonery, earthy common sense, business acumen and lofty ambition.

The poster for the premiere |

Rushton adds that Papageno properly steals the show, as he should, as his journey to domestic fulfillment is closer to normal human experience than the lofty outcome of prince and princess.

Zauberfl�te was a phenomenal success – and remarkably so, in view of its essentially subversive view of the repressive social, religious and political environment of the time. While there are few contemporary accounts, in a letter to his wife one week after the premiere Mozart wrote: "I just got back from the opera. It was just as full as always." After detailing the many encores, he continued: "But what pleases me most is the silent approval. � One can see well how much, and increasingly so, the opera is gaining esteem." Two days later he again wrote of the "packed house with usual applause and encores." (In the same letter he chastised a patron who laughed throughout. Yet his irrepressible spirit remained, as he related a practical joke – he slipped into the orchestra and played slower arpeggios on Papageno's chimes so that it became obvious that Schikaneder was not playing them himself. Perhaps that letter provides a key clue to the ideal tone Mozart intended, deftly balanced between lighthearted and earnest, amusing yet pensive, engaging yet heartfelt.)

Schickaneder's theater performed Zauberfl�te 24 times in the first five weeks alone and retained exclusive rights for a year, but then it spread quickly and was translated into Italian, Czech, Polish, Swedish, Russian and English and met with a great reception. In 1793 the Berlin Musikalische Zeitung reported: "Everything is turned to magic at these theatres – there are the magic flute, the magic ring, the magic crown, the magic arrow, the magic mirror and many other wretched magic affairs. Words and music are equally contemptible, except for the Magic Flute." Not all productions were authorized or authentic. The most notorious was a French adaptation, Les Myst�res d'Isis, with characters renamed, text rewritten, recitatives added, the music cut and recomposed, and arias substituted from other popular Mozart operas and even a Haydn symphony – Berlioz called it "Mozart assassinated." In an era in which audiences craved new works and most operas were quickly forgotten Zauberfl�te endured and thrived. Mozart's first biographer, Franz Xavier Neiemetschek, wrote in 1798: "What shall I say about the Zauberfl�te? Who in Germany does not know it?  Is there a theatre in which it was not performed? It is our national piece. The applause it received everywhere – everywhere from the court theater to the wandering troupe in a small market town, is yet without parallel." Is there a theatre in which it was not performed? It is our national piece. The applause it received everywhere – everywhere from the court theater to the wandering troupe in a small market town, is yet without parallel."

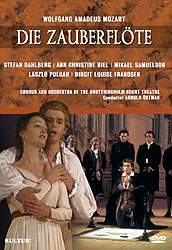

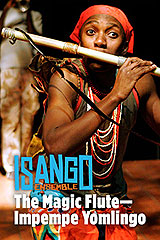

Compelling proof of the enduring universal appeal of Zauberfl�te lies in the bold, imaginative decor it has inspired, stemming from the fantastic early 19th century designs by Karl Friedrich Schinkel and Simon Quaglio, depicted at the beginning and end of this article, through a wide range of modern presentations. Some attempt to replicate the sound of the original – a 2000 Kultur video presents the Drottningham Court Theatre troupe led by Arnold �stman in a theater dating from 1776, complete with wigged musicians in frilly shirts playing period instruments and using technology of the time, including a rather bare stage with painted flats and backdrops, nominal props, the Three Women rising from a trapdoor, the Three Boys floating down on a swing from the flyspace, and minimal lighting effects for rather anemic fire and water trials and the Queen's demise, Compelling proof of the enduring universal appeal of Zauberfl�te lies in the bold, imaginative decor it has inspired, stemming from the fantastic early 19th century designs by Karl Friedrich Schinkel and Simon Quaglio, depicted at the beginning and end of this article, through a wide range of modern presentations. Some attempt to replicate the sound of the original – a 2000 Kultur video presents the Drottningham Court Theatre troupe led by Arnold �stman in a theater dating from 1776, complete with wigged musicians in frilly shirts playing period instruments and using technology of the time, including a rather bare stage with painted flats and backdrops, nominal props, the Three Women rising from a trapdoor, the Three Boys floating down on a swing from the flyspace, and minimal lighting effects for rather anemic fire and water trials and the Queen's demise,  focusing instead upon hugely expressive acting – Papagena fairly bursts with wholesome lust. At the other extreme is a two-hour 2014 radical reworking by the South African Isango Ensemble that shifts the opera to a context of African folk-tales and communal initiation rites, full of singing, dancing, drumming, and an orchestra of marimbas, oil barrels and a jazz trumpet. focusing instead upon hugely expressive acting – Papagena fairly bursts with wholesome lust. At the other extreme is a two-hour 2014 radical reworking by the South African Isango Ensemble that shifts the opera to a context of African folk-tales and communal initiation rites, full of singing, dancing, drumming, and an orchestra of marimbas, oil barrels and a jazz trumpet.

Perhaps the most widely-known adaptation is the affectionate 1975 Ingmar Bergman movie that features droll backstage business (Papageno awakens from a snooze in time to go on; Tamino and Pamina play chess during the intermission), magic (Pamina's portrait comes to life; chattering skulls accompany the Three Ladies tempting Tamino to speak), intimacy (whispering and closeups that an actual theater audience would never perceive), departures from the original plot (Sarastro assures Pamina that the entire episode with Monostatos and her mother was a nightmare; after she and Tamino emerge from their trials he cedes leadership of the temple to them), and transcending theatrical confines (a torchlight parade for Sarastro's first entrance; Tamino and Pamina's literal passage through fire) – all seen appropriately through the awe-struck eyes of a young girl (Bergman's daughter, in annoyingly frequent and sustained cut-away shots) and an equally apt racially-diverse audience. Far bolder is a 2006 Kenneth Branaugh movie that transposes the opera to a World War I battlefield and replaces all allusions to Masonic creed with pacifism (Tamino's trial becomes a mission seeking a cease-fire). At first it sounds like a mere parody – the overture is overwhelmed by the din of combat, Tamino is rescued from poison gas by three nurses, Papageno is a handler of carrier pigeons, the Queen commands a tank and Sarastro heads a convalescent ward – but ultimately it's redeemed by fine singing, witty English-language lyrics and vivid direction. While computer effects, creative photography and spectacular opening and final shots leave the 18th century far behind, its underlying humanism remains fully intact and is genuinely moving. – the overture is overwhelmed by the din of combat, Tamino is rescued from poison gas by three nurses, Papageno is a handler of carrier pigeons, the Queen commands a tank and Sarastro heads a convalescent ward – but ultimately it's redeemed by fine singing, witty English-language lyrics and vivid direction. While computer effects, creative photography and spectacular opening and final shots leave the 18th century far behind, its underlying humanism remains fully intact and is genuinely moving.

These reconceptions, in turn, raise the issue of the extent to which it is appropriate to modernize a work that was written to suit the limitations and audience expectations of its time.  On a practical level, Anthony Besch notes that Schikaneder and Mozart structured their opera so as to maximize its impact through the dramatic effects of their era. Thus, he suggests that rudimentary technology was accepted, if not expected, as standard elements of the theatrical experience and that some of the music was intended to disguise the noise of the baroque mechanisms needed for scene changes. Gustuv Sellner further contends that the now largely obsolete effects of Mozart's time propelled his audiences into a realm of fantasy that can only be compromised by realistic sets, electric lighting and the other resources of modern theater. Yet we cannot simply ignore two centuries' evolution and sophistication that have created an unbridgeable gulf with Mozart's esthetic, which now is apt to appear merely quaint rather than openly sincere and convincing. So perhaps updating is needed to establish a viable link to modern audiences. Should producers attempt to transport us back to a long-forgotten cultural world, or should they accept that updated technology is needed to stimulate emotional acceptance of the underlying essence of the work? On a practical level, Anthony Besch notes that Schikaneder and Mozart structured their opera so as to maximize its impact through the dramatic effects of their era. Thus, he suggests that rudimentary technology was accepted, if not expected, as standard elements of the theatrical experience and that some of the music was intended to disguise the noise of the baroque mechanisms needed for scene changes. Gustuv Sellner further contends that the now largely obsolete effects of Mozart's time propelled his audiences into a realm of fantasy that can only be compromised by realistic sets, electric lighting and the other resources of modern theater. Yet we cannot simply ignore two centuries' evolution and sophistication that have created an unbridgeable gulf with Mozart's esthetic, which now is apt to appear merely quaint rather than openly sincere and convincing. So perhaps updating is needed to establish a viable link to modern audiences. Should producers attempt to transport us back to a long-forgotten cultural world, or should they accept that updated technology is needed to stimulate emotional acceptance of the underlying essence of the work?

Although the question will continue to inform new productions, there can be no definitive answer. But it is quite clear that, whether its presentations are period or modern, straightforward or wildly inventive (or, more likely, somewhere within these extremes), there appears to be no end in sight for Zauberfl�te to enchant future generations – according to Operabase in the 2012-13 season Zauberfl�te was the fourth most frequently performed opera worldwide, exceeded only by La traviata, Carmen and La boh�me.

Zauberfl�te was by far the greatest success of Mozart's life, but he died nine weeks after the premiere, at the mere age of 35. (Christopher Raeburn notes the bitter irony that only a few years later the kidney disease that hastened Mozart's end became curable.) Zauberfl�te was by far the greatest success of Mozart's life, but he died nine weeks after the premiere, at the mere age of 35. (Christopher Raeburn notes the bitter irony that only a few years later the kidney disease that hastened Mozart's end became curable.)  Reportedly, each evening on his deathbed he imagined the progress of that night's performance and wished that he could hear Zauberfl�te one more time. Mozart's untimely demise raises the absorbing prospect of how he might have further altered the course of music had he enjoyed normal adult longevity. At a bare minimum Robert L. Marshall contends, "genius never ceases to grow," and that Mozart, "arguably the most gifted musical genius in history, would have continued to produce masterpieces of the highest order." But beyond that, consider two startling facts which Marshall recounts. Reportedly, each evening on his deathbed he imagined the progress of that night's performance and wished that he could hear Zauberfl�te one more time. Mozart's untimely demise raises the absorbing prospect of how he might have further altered the course of music had he enjoyed normal adult longevity. At a bare minimum Robert L. Marshall contends, "genius never ceases to grow," and that Mozart, "arguably the most gifted musical genius in history, would have continued to produce masterpieces of the highest order." But beyond that, consider two startling facts which Marshall recounts.

First, in 1790 when Johann Peter Salomon engaged Haydn to come to England to present concerts of new works for a year, he also engaged Mozart, who was to follow in 1792. During his stay in London Haydn was transformed – he was besieged with invitations, feted with extraordinary honors, and earned a fortune. One can only imagine the impact of a similar experience upon Mozart, who was struggling financially and was increasingly marginalized by local patrons. Marshall speculates that he might have become disgusted with the increasingly intolerant and repressive Viennese regime, been attracted to opportunities of the New World, and even eased into the role of a music professor in New York.

Second, in 1787 a promising teenager came to Vienna to study composition with Mozart but immediately had to return to Bonn to tend to his sick mother. When he returned in 1792 Mozart was no more and he had to take lessons from Haydn instead. The impressionable novice was none other than Beethoven! We can only marvel at the worlds that Mozart's sweeping but disciplined brilliance might have opened for Beethoven and the different course his own genius, and music itself, might have taken.

Complete sets would come later, but first there were recordings of arias – lots of them. Whether due to the variety and abundance of individual pieces in the singspiel design or their inherent appeal, the sheer number of Zauberfl�te excerpts surpassed those from Mozart's other operas. Thus Alan Kelly's compilation of German Gramophone recordings from 1898-1929 found 106 of Zauberflote arias, compared to 76 from Figaro and 54 from Don Giovanni. Complete sets would come later, but first there were recordings of arias – lots of them. Whether due to the variety and abundance of individual pieces in the singspiel design or their inherent appeal, the sheer number of Zauberfl�te excerpts surpassed those from Mozart's other operas. Thus Alan Kelly's compilation of German Gramophone recordings from 1898-1929 found 106 of Zauberflote arias, compared to 76 from Figaro and 54 from Don Giovanni.  Of those, the most frequently recorded was "O Isis und Isiris" (a basso favorite – 22 different versions), followed by "Dies Bildnis" (Tamino's loving adoration of Pamina's portrait – 17), "In diesen heil' gen Hallen" (a coloratura display – 14) and "Bei M�nnern" (in which Pamina and Papageno look forward to their respective loves – 10). Less popular were Pamina's outpouring of grief, "Ach, ich f�hls", the Queen's other torrent, "Der H�lle Rache", the charming Papageno-Papagena duet and, most surprisingly, perhaps the best known aria nowadays, and surely one of the catchiest, Papageno's "Der Vogelf�nger bin ich ja." Similarly the comprehensive Center for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music [CHARM] discography of the entire 78 rpm era, drawn from diverse sources, lists 709 Zauberfl�te 78s with the most popular again being "O Isis," "Dies Bildnis" and "In diesen heil'," now joined by "Ach, ich f�hls" and "Der H�lle Rache" – but not Papageno's aria or "Bei M�nnern." Of those, the most frequently recorded was "O Isis und Isiris" (a basso favorite – 22 different versions), followed by "Dies Bildnis" (Tamino's loving adoration of Pamina's portrait – 17), "In diesen heil' gen Hallen" (a coloratura display – 14) and "Bei M�nnern" (in which Pamina and Papageno look forward to their respective loves – 10). Less popular were Pamina's outpouring of grief, "Ach, ich f�hls", the Queen's other torrent, "Der H�lle Rache", the charming Papageno-Papagena duet and, most surprisingly, perhaps the best known aria nowadays, and surely one of the catchiest, Papageno's "Der Vogelf�nger bin ich ja." Similarly the comprehensive Center for the History and Analysis of Recorded Music [CHARM] discography of the entire 78 rpm era, drawn from diverse sources, lists 709 Zauberfl�te 78s with the most popular again being "O Isis," "Dies Bildnis" and "In diesen heil'," now joined by "Ach, ich f�hls" and "Der H�lle Rache" – but not Papageno's aria or "Bei M�nnern."  However, by mid-century Giovanni (with 728) had caught up with Zauberfl�te in overall popularity and Figaro (with 599) nearly so – although, for perspective, Carmen trumped them all with an astounding 2,421. (The data compiled by The World's Encyclopedia of Recorded Music [WERM], covering the monaural electrical era (1925-56), yields a roughly comparable tally.) However, by mid-century Giovanni (with 728) had caught up with Zauberfl�te in overall popularity and Figaro (with 599) nearly so – although, for perspective, Carmen trumped them all with an astounding 2,421. (The data compiled by The World's Encyclopedia of Recorded Music [WERM], covering the monaural electrical era (1925-56), yields a roughly comparable tally.)

The relative few I've heard are fascinating, as they recall the deeply personal performance style prevalent a century ago but now deemed inappropriate for Mozart and thus obsolescent. Among those collected on the EMI Les Introuvables du Chant Mozartien LP and CD sets, there's tangible pain in Emmy Destinn's 1908 "Ach, ich f�hls," deep longing in Marcel Wittrich's 1929 "Dies Bildnes," utter command in Lev Sibiriakov's 1911 "In diesen heil'gen Hallen" (in Russian), playful pauses in Lucien Fug�re's 1929 "Der Vogelf�nger bin ich ja" (in French), and – most incredible of all – a 1906 "Der H�lle Rache" in which Maria Galvany tears through the staccato acrobatics at an insanely fast tempo in order to save time to dazzle with her stratospheric high notes in an unabashedly unstylish cadenza.

At the outset, it seems only fair (and rather obvious) to acknowledge that audio-only recordings severely distort the total experience of opera, of which singing is only one component along with acting and the overall display. Many opera stars through the ages were famed as much for their stage presence as their vocal skills. At the outset, it seems only fair (and rather obvious) to acknowledge that audio-only recordings severely distort the total experience of opera, of which singing is only one component along with acting and the overall display. Many opera stars through the ages were famed as much for their stage presence as their vocal skills.

Yet, despite the creators' intentions, for nearly a century the vast majority of us have encountered opera through audio alone. Telecasts and videos now can remedy at least part of the imbalance of the essential components, but that's a recent advance. The fact remains that for nearly the entire era of recording only the musical portions of operas were preserved and as a result nearly all our tangible evidence of opera performance has been concentrated into audio (and for the first two generations on record, only snippets in primative fidelity). While it may be unfair to judge the great artists of the past solely by the traces of their voices (and a few still pictures, film clips and commentaries), technology has left us no choice.

Please note that the following is not intended to be a thorough survey. Rather, of the complete Zauberfl�te recordings compiled by Operadis (128 as of 2009!), I've focused on those that impress me as having particular historical or stylistic interest. Even so, for those for whom digital recording is an absolute must (and I pity you – you�re cutting yourself off from so much fabulous stuff!), I can wholeheartedly endorse several digital Zauberfl�tes among those I�ve heard, although they lack the historical and/or esthetic significance of their predecessors:

- for a lush, traditional approach: Levine/Vienna (RCA, 1980; 174� – at first issued only on analogue vinyl with a now-quaint note of regret that neither software nor hardware then existed for digital home listening, and looking foward to the day when that would become possible)

- for an historically-informed reading: either �stman/Drottningham (Oiseau-Lyre, 1992; 156� – nicely burnished) or Christie/Les Arts Florissants (Erato, 1995; 150� – with some idiosyncratic but effective tempo touches)

- for an effective balance between the two stylistic poles (and striking covers): Harnoncourt/Zurich (Teldec, 1987; 144� – patient tempos and careful balances but a Queen with wobbly vibrato) or Abbado/Mahler Chamber Orchestra (DG, 2005; 149� – crisp, clean and invigorating, with musical emphases rather than sound effects)

- and a rare budget edition (but check for budget reissues or on-line availability of the others): Halasz/Failoni (Naxos, 1993; 150� – rather bland and not as committed or inspired as the others but decent enough and fair value for the price)

With that out of the way, let's return to the beginning. The headnotes are formatted as follows: the conductor; the singers of Tamino, Pamina, Papageno, Papagena, Sarastro and the Queen; the orchestra (year; original label, the source I've heard (if different); and the duration). Note that the timings can be far more meaningful as an indication of the amount of dialog than tempo.

- Sir Thomas Beecham; Helge Roswaenge, Tiana Lemnitz, Gerhard H�sch, Irma Geilke, Wilhelm Strienz, Erna Berger; Berlin Philharmonic (1937-38; HMV 78s, Naxos CD; 130' [no dialog])

Beginning in 1935, the Mozart Opera Society bestowed on record collectors (wealthy ones, anyway) fabulous annual bounties – the first complete recordings of Figaro, Cosi and Giovanni, all in conjunction with productions of the newly-founded Glyndebourne Festival led by Fritz Busch, recently forced out of his eminent position at the Dresden State Opera. Next was to have been Zauberfl�te, but plans were cancelled when the Society's producer arranged to record it in Berlin with Sir Thomas Beecham.  As one annotator gingerly put it, "It is sometimes suggested that political considerations were a factor in the selection of the cast and that some more celebrated or experienced singers might otherwise have been chosen to take part." Translation: no Jews allowed. Despite his fame and artistic taste, no one ever accused Beecham of having political scruples, and he readily agreed to replace with Aryans his Tamino (Richard Tauber, whose father was born Jewish but converted) and his Sarastro (Alexander Kipnis, a Russian-born Jew and arguably the finest bass in Europe), as well as several Jewish members of the Berlin Philharmonic. As one annotator gingerly put it, "It is sometimes suggested that political considerations were a factor in the selection of the cast and that some more celebrated or experienced singers might otherwise have been chosen to take part." Translation: no Jews allowed. Despite his fame and artistic taste, no one ever accused Beecham of having political scruples, and he readily agreed to replace with Aryans his Tamino (Richard Tauber, whose father was born Jewish but converted) and his Sarastro (Alexander Kipnis, a Russian-born Jew and arguably the finest bass in Europe), as well as several Jewish members of the Berlin Philharmonic.

Despite requiring eight sessions spread over three months (plus a ninth for "O Zittre Nicht" conducted by Bruno Seidler-Winkler), the continuity is remarkable, and the cast inhabit their roles without distorting the musical flow – Tamino is convincingly heroic, Papageno proudly oblivious, Pamina ingenuous yet knowing, Sarastro imposing but imbued with spirituality, Monostatos sharp and piercing. The only exceptions to my ears are the Queen, sounding a bit too girlish (yet thus adding poignancy to the role) and the three boys, here (as would become routine) sung by mature-sounding women who thus deprive the roles of their charm and innocence. Beecham unifies the production with the same incomparable sense of moderation and balance for which his pioneering recordings of Mozart symphonies and concerti were celebrated, leaving no doubt that this is a wonderful fantasy that shouldn't be taken too seriously. All dialog was omitted – understandably so, since the music alone consumed a back- and wallet-breaking 19 12" discs – but the need to change records provided some of the needed buffer between numbers (missing from LP and CD transfers). Fidelity is decent if a bit blurred. Far from an historical relic, and despite dozens of new contenders, the authority and sheer excellence of this first recorded Zauberfl�te remain touchstones that still delight and prevent it from ever becoming pass�.

- Arturo Toscanini; Helge Roswaenge, Jarmila Novotna, Willi Dormgraf-Fassbaender, Dora Komarek, Alexander Kipnis, Julia Osvath; Vienna Philharmonic (live, Salzburg Festival, July 30, 1937; Melodram and Naxos CDs; 155')

Toscanini's Mozart could be dismissed as dry, rigid and graceless. That's largely true of his late NBC studio symphony and concerto recordings by which his legacy tends to be judged and remembered nowadays.  Yet that's not entirely fair – his 1929 New York Philharmonic Mozart Symphony # 35 is terrifically pliant and exquisite. Harvey Sachs notes that Toscanini championed Zauberfl�te, reintroducing it to La Scala (where it hadn't been heard in 107 years) in 1923, and when audiences, unused to dialog, scorned it as an undignified operetta and demanded it be withdrawn, was outraged and defiantly scheduled it again the following year. This recording is historic – Toscanini's final presentation of a fully-staged opera – but it presents a severe challenge. It was taken down on the Selenophone, a precursor of tape recording that used a light beam to expose an optical photographic soundtrack on unperforated 7mm film running at about two feet per second. In theory, the quality should have been excellent, comparable to 35 mm movies, and fully reproducible as positive prints with no loss of fidelity. But while the original elements apparently exist in an archive, all current editions are derived from badly depreciated dubs afflicted with crude sound, loads of distortion and occasionally severe wow. Sonics aside, balances are skewed, with singers occasionally way off-mike and overwhelmed by timpani that make for terrifying thunder but otherwise distend the texture with exaggerated accents. Yet, the general prominence of the orchestra enables us to focus on Toscanini's light, sincere and dignified approach, as well as the splendor of Mozart's scoring (often submerged beneath vocals in early recordings) that can still be inferred through the sonic veil. With some irony, Spike Hughes attributes Toscanini's success with Zauberfl�te to his lack of sophistication that led to superficial renditions of the other mature Mozart operas, but here such na�vet� yields rewards. Indeed, Toscanini's approach is simple, invigorating and classical, avoiding sentimentality at the cost of Romantic harbingers or any philosophical depth. The singing is generally fine and striking in its unaffected innocence (strangely contrasting with highly emotive vocal "acting" reserved for the spoken interludes), although the lengthy stretches of dialog, at times barely audible above the considerable noise, tend to drag. Interestingly, Sachs notes that as a means of enhancing continuity between spoken and sung portions Toscanini had his singers modulate their dialog into the key of an upcoming musical number (although frankly I don't hear it). Kipnis, booted by Beecham, is a compelling Sarastro. Despite Toscanini's reputed insistence upon adherence to the score, his Three Boys are women. Despite the sonic hurdles, Toscanini's Zauberfl�te testifies to the intensity of his focus and resistance to interpretive inflection, and thus points the way toward the historically-informed outlook of a later generation. Yet that's not entirely fair – his 1929 New York Philharmonic Mozart Symphony # 35 is terrifically pliant and exquisite. Harvey Sachs notes that Toscanini championed Zauberfl�te, reintroducing it to La Scala (where it hadn't been heard in 107 years) in 1923, and when audiences, unused to dialog, scorned it as an undignified operetta and demanded it be withdrawn, was outraged and defiantly scheduled it again the following year. This recording is historic – Toscanini's final presentation of a fully-staged opera – but it presents a severe challenge. It was taken down on the Selenophone, a precursor of tape recording that used a light beam to expose an optical photographic soundtrack on unperforated 7mm film running at about two feet per second. In theory, the quality should have been excellent, comparable to 35 mm movies, and fully reproducible as positive prints with no loss of fidelity. But while the original elements apparently exist in an archive, all current editions are derived from badly depreciated dubs afflicted with crude sound, loads of distortion and occasionally severe wow. Sonics aside, balances are skewed, with singers occasionally way off-mike and overwhelmed by timpani that make for terrifying thunder but otherwise distend the texture with exaggerated accents. Yet, the general prominence of the orchestra enables us to focus on Toscanini's light, sincere and dignified approach, as well as the splendor of Mozart's scoring (often submerged beneath vocals in early recordings) that can still be inferred through the sonic veil. With some irony, Spike Hughes attributes Toscanini's success with Zauberfl�te to his lack of sophistication that led to superficial renditions of the other mature Mozart operas, but here such na�vet� yields rewards. Indeed, Toscanini's approach is simple, invigorating and classical, avoiding sentimentality at the cost of Romantic harbingers or any philosophical depth. The singing is generally fine and striking in its unaffected innocence (strangely contrasting with highly emotive vocal "acting" reserved for the spoken interludes), although the lengthy stretches of dialog, at times barely audible above the considerable noise, tend to drag. Interestingly, Sachs notes that as a means of enhancing continuity between spoken and sung portions Toscanini had his singers modulate their dialog into the key of an upcoming musical number (although frankly I don't hear it). Kipnis, booted by Beecham, is a compelling Sarastro. Despite Toscanini's reputed insistence upon adherence to the score, his Three Boys are women. Despite the sonic hurdles, Toscanini's Zauberfl�te testifies to the intensity of his focus and resistance to interpretive inflection, and thus points the way toward the historically-informed outlook of a later generation.

- Herbert von Karajan; Anton Dermota, Irmgard Seefried, Erich Kunz, Emmy Loose, Ludwig Weber, Wilma Lipp; Vienna Philharmonic (1950; EMI CD; 129' [no dialog])

- Wilhelm Furtw�ngler; Anton Dermota, Irmgard Seefried, Erich Kunz, Edith Oravez, Josef Greindl, Wilma Lipp; Vienna Philharmonic (live, Salzburg Festival, August 1, 1951; EMI CD or Pristine download; 175')

These two contemporaneous recordings boast the same orchestra and virtually identical casts, and there lies a tale. As recounted by Sam Skirakawa, Furtw�ngler had prepared and led Zauberfl�te at the annual Salzburg Festival and had a "gentleman's agreement" with renowned EMI producer Walter Legge to record it. But despite his high musical standards and brilliant results, few would accuse Legge of being a gentleman – his associate Anthony Griffith said he "would stab you in the back if it suited his purpose. � He was the rudest man I have ever come across. � Once you ceased being of use he would turn on you and do anything." (And yes, he's the same producer who had snatched the Beecham Zauberfl�te from Glyndebourne.)   In late 1950, when he was recording Figaro with Karajan, using the same cast and orchestra that had been primed by Furtw�ngler, Legge surreptitiously added sessions to tape Zauberfl�te as well. When Furtw�ngler discovered the deception, he hotly protested the "outrageous personal breach of trust," his "public humiliation" and the "personal affront." Legge simply shrugged it off, as they had no contract. At first, Furtw�ngler threatened to resign from EMI altogether, but then backed off and simply refused to work with Legge. In late 1950, when he was recording Figaro with Karajan, using the same cast and orchestra that had been primed by Furtw�ngler, Legge surreptitiously added sessions to tape Zauberfl�te as well. When Furtw�ngler discovered the deception, he hotly protested the "outrageous personal breach of trust," his "public humiliation" and the "personal affront." Legge simply shrugged it off, as they had no contract. At first, Furtw�ngler threatened to resign from EMI altogether, but then backed off and simply refused to work with Legge.

Fortunately, we have two live recordings of Furtw�ngler's Salzburg Zauberfl�te performances to compare to the Karajan studio set – and there's quite a difference indeed. Karajan leads a thoroughly idiomatic performance dominated by beautiful singing and smoothly blended ensembles – perhaps too sweet, as there is little sense of character and neither the Queen nor Monostatos project much menace. His accompaniments constantly defer to the soloists' proclivities of tempo, volume and expression, with little attempt to forge any dramatic sense beyond that inherent in the music. Even so, given the splendor of Mozart's achievement, and especially since all the dialog is omitted, that's not necessarily a condemnation, as it affords an opportunity to revel in the music itself.

Under Furtw�ngler's baton the cast undergoes a remarkable transformation – just as imposing but now charged with commitment, vitality and purpose. Tempos tend to be slow, but always focused without ever becoming grim. While never losing sight of the sublimation of overt feeling that is so essential to Mozart's art, the entire opera flows with the added sensation of philosophical weight. Even without an understanding of German, we can constantly sense the emotional import, as from the very outset each phrase is inflected for meaning – the overture tentatively peers ahead into the unknown, the Three Ladies keenly compete for dominance rather than flitting about in playful flirtation, Tamino aches over Pamina's portrait, and the Queen's coloratura is a mere heady flourish rather than the climax of her anguish. (Curiously, though, subtlety is limited to the music – as with the Toscanini staging, the dialog tends to be flamboyant.) Furtw�ngler viewed Zauberfl�te in terms of Mozart's humanity and conveys that perspective throughout – a profoundly moving experience that overcomes any banality of the text and transcends the specific plot, characters and rites to convey universal truths.

- Ferenc Fricsay; Ernst H�fliger, Maria Stader, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Lisa Otto, Josef Greindl, Rita Streich; RIAS Symphony Orchestra, Berlin (1955; DG [US: Decca] LP; 143')

Not only is this the first studio recording of Zauberfl�te to include dialog, but it goes to the extraordinary luxury of separate principal casts for song and speech (except for Maria Stader as the Queen, who admittedly has only a few spoken lines, and Lisa Otto as Papagena, who apparently was entrusted with her own recitation, despite the huge gulf between her emulation of a shrill old crone and her sung ing�nue role).    But why bother? Did the producers really feel that Fischer-Dieskau, already one of the world's preeminent lieder singers and renowned for his exceptionally sensitive expression, was incapable of projecting his character in speech? The double-casting effort goes beyond questionable to self-defeating as it severely impairs integration of the two elements of singspiel into a unified whole. Rather there are constant abrupt shifts in vocal texture and volume between dialog and song (Pamina/speaker has a far deeper and softer voice than Pamina/singer), and the recitations tend to be paced more slowly, with many presumably meaningful pauses, than the music, for which Fricsay provides a generally light and buoyant texture. At the same time, several of the actors' voices are too similar to each other, and the resulting confusion is compounded by the monaural sound that deprives them of any spatial location that would help to differentiate them. Thus the lengthy initial exchange between Tamino and Papagano sounds like a continuous monologue of a single character and requires careful following of a libretto to distinguish the two characters. (Ironically, the singers' own voices are sufficiently distinctive from one another as to have avoided such problems.) While the musical content is quite stylish and enjoyable, this set testifies to the damage that misguided producers can cause to a worthy artistic venture. Nowadays the problem can be tempered, as the current CD edition tracks the musical portions separately from the dialog that can be programmed out – an inconvenience but a remedy unavailable to the original LP buyers. But why bother? Did the producers really feel that Fischer-Dieskau, already one of the world's preeminent lieder singers and renowned for his exceptionally sensitive expression, was incapable of projecting his character in speech? The double-casting effort goes beyond questionable to self-defeating as it severely impairs integration of the two elements of singspiel into a unified whole. Rather there are constant abrupt shifts in vocal texture and volume between dialog and song (Pamina/speaker has a far deeper and softer voice than Pamina/singer), and the recitations tend to be paced more slowly, with many presumably meaningful pauses, than the music, for which Fricsay provides a generally light and buoyant texture. At the same time, several of the actors' voices are too similar to each other, and the resulting confusion is compounded by the monaural sound that deprives them of any spatial location that would help to differentiate them. Thus the lengthy initial exchange between Tamino and Papagano sounds like a continuous monologue of a single character and requires careful following of a libretto to distinguish the two characters. (Ironically, the singers' own voices are sufficiently distinctive from one another as to have avoided such problems.) While the musical content is quite stylish and enjoyable, this set testifies to the damage that misguided producers can cause to a worthy artistic venture. Nowadays the problem can be tempered, as the current CD edition tracks the musical portions separately from the dialog that can be programmed out – an inconvenience but a remedy unavailable to the original LP buyers.

- Karl B�hm; Leopold Simoneau, Hilde Gueden, Walter Berry, Emmy Loose, Kurt B�hme, Wilma Lipp; Vienna Philharmonic (1954; Decca [US: London] LP; 133' [no dialog])