|

We tend to think of great music – and indeed all art – as universal and timeless, transcending the specific circumstances of inspiration.  Thus Beethoven may have penned his "Eroica" Symphony in tribute to Napoleon, but its potent subtext of heroism, grief and triumph resonate 200 years later and undoubtedly will be equally effective for generations to come. Thus Beethoven may have penned his "Eroica" Symphony in tribute to Napoleon, but its potent subtext of heroism, grief and triumph resonate 200 years later and undoubtedly will be equally effective for generations to come.  Yet, some works, while continuing to speak to us across the ages, are very much of their time – from Handel's Water Music conjuring the splendor of baroque royalty to George Crumb's Black Angels evoking the confusion and pain of the Vietnam War. Die Dreigroschenoper ("The Threepenny Opera") unmistakably recalls Berlin on a precipice between the World Wars, when the vacuum of its shattered culture eagerly embraced new influences, especially the intrigue of American movies and jazz, with a decadent zest fueled by the desperation of a crashed economy and social unrest, and yet resonates in our own time as well. Yet, some works, while continuing to speak to us across the ages, are very much of their time – from Handel's Water Music conjuring the splendor of baroque royalty to George Crumb's Black Angels evoking the confusion and pain of the Vietnam War. Die Dreigroschenoper ("The Threepenny Opera") unmistakably recalls Berlin on a precipice between the World Wars, when the vacuum of its shattered culture eagerly embraced new influences, especially the intrigue of American movies and jazz, with a decadent zest fueled by the desperation of a crashed economy and social unrest, and yet resonates in our own time as well.

Despite its relevance to Berlin of the 1920s, the Threepenny Opera had its origins in London two full centuries earlier. John Gay's 1727 Beggar's Opera had created a sensation by skewering the conventions (and pretensions) of trendy Italianate opera and its florid arias, noble characters and rigid morality.

William Hogarth print of the Beggar's Opera, depicting the characters as animals |

Gay's work introduced a new genre, the "ballad opera," in which bawdy common folk warbled popular tunes while adrift in life's problems. The music of the Beggar's Opera, arranged by Johann Pepusch, boasted an overture and 68 brief songs that pop up every minute or so, all broadside ballads or other well-known melodies with new and often satiric lyrics (thus "Oh London is a Fair Town" became "Our Polly is a Sad Slut"). The wacky plot involves Polly Peacham, whose parents run a lucrative fencing ring and are upset that she's secretly married the robber Macheath – until they realize that they can make her a wealthy widow by claiming the reward for turning him in to be hanged. After swearing to be faithful, Macheath heads to his favorite whorehouse, where former lover Jenny betrays him. The musical highlight is a soliloquy in which the imprisoned Macheath, torn between the affections of Polly and Lucy, the jailer's flirty daughter, darts through snatches of ten songs to express the varying moods of his despair. In a final twist, Macheath is about to be hanged but is spared because audiences should leave happy although, as the narrator warns, both rich and poor sin while only the poor are punished.

The Beggar's Opera was a huge success – as one critic of the time noted, it made Rich (the theatre owner) very gay and Gay very rich. A 1922 London revival struck a deeply responsive chord in Bertolt Brecht, whose secretary, Elizabeth Hauptmann, brought it to his attention and prepared a translation.

Bertolt Brecht |

A Marxist poet and playright, Brecht was evolving a notion of "epic drama" that would appeal to the masses rather than to the elite, reflect the reality of existence rather than idealism, and promote didacticism and reflection over emotion. Brecht was struck by the resonance with the ferment of Berlin, in which hypocritical entrepreneurs were living off rather than by the established moral codes. The Beggar's Opera seemed an ideal vehicle to condemn bourgeois convention and agitate for social change. An incessant borrower, Brecht had no compunction against building on the past; as one defender noted, he "stole with genius." At first he wanted to call his adaptation Gerindel ("Scum"), then Ludenoper ("The Pimp's Opera") and finally seized upon Die Dreigroshenoper ("The Threepenny Opera"), by which he meant a work beggars could afford but so splendid in concept that only beggars could imagine it.

His ideal collaborator for the project was Kurt Weill, a young Berlin composer who had already written several short operas in which he had sought to expand theatrical convention.

Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya |

As recalled by his wife, Lotte Lenya, Weill had read some of Brecht's poems and found a counterpart to his own outlook and goals of bridging the gap between serious art and public taste. Their first project, Mahagonny-Songspiel, linked five Brecht poems into a sketchy half-hour tale of idealism, depravity and disillusionment in a mythical city in the exotic locale of South Florida, and had polarized audiences at the 1927 Baden-Baden festival – a "reverse scandal" whose traditional sound shocked through its lack of the expected cutting-edge modernity. The score (which Brecht and Weill would later expand into a full opera, Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny – Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny) includes "Alabama Song" (originally sung in "exotic" English), of which the Doors provided a surprisingly credible rendition on their first album.

Brecht had been approached by Ernest-Josef Aufricht, who desperately needed a work to draw attention to his new Schiffbauerdamm Theatre in Berlin. With a mere three months until the opening, Brecht and Weill closeted themselves on the Riviera and emerged with a novel approach that infused old forms with new ideas, as had been urged by Weill's teacher, Ferrucio Busoni. As Dr. J�rgen Schebera has since noted, Brecht cobbled his lyrics from a deliberately awkward, arrhythmic and repetitious mix of Biblical quotations, tired clich�s and street slang, and Weill's music draws upon and abruptly shifts among classics, popular dance tunes and jazz. Indeed, much of the work's energy derives from these constant multi-leveled tensions, thus perhaps symbolizing the Marxian principle so dear to Brecht of progress arising from a synthesis of opposites.

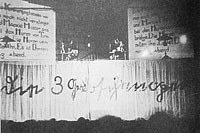

The presentation was intended to counteract the gritty plot. Weill and Brecht drew a clear division between story and song. In so doing, they recalled the origins of opera,

The half-curtain and projected slides in the original production |

in which lengthy arias intruded into essentially theatrical dramas, and distanced themselves from Wagnerian practice, in which operas were through-composed, with arias smoothly blended into the narrative. Indeed, the songs brazenly interrupted the action and were announced by lighting changes and projected slides. The roles were cast with actors rather than trained singers, who spoke their lines rhythmically and with vague intonation, their easy linear melodies often doubled by an instrument. (Interestingly, perhaps as an accommodation to modern expectations of vocal skill, both recordings of the original Beggar's Opera use separate casts for the dialogue and singing.) A seven-piece band sat at the rear of the stage surrounding a fairground pipe organ, and a seedy half-curtain hung from a rod, as if to only barely disguise the theatrical artifice, while amply flaunting a rag-tag attitude.

Pre-production snags included last-minute cast changes, Weill's fury upon discovering that his wife's name had been omitted from the program, producers' misgivings so severe that they had their musical director prepare the original Pepusch score as a stand-by,

The 1931 Pabst movie:

The Street Singer's Moritat |

and the lead actor's vain demand for a striking entrance. To cure the last problem, Brecht and Weill wrote a new number overnight, based on authentic street-fair singers' recitations of the crimes of notorious criminals. As the "Moritat von Meckie Messer," Weill quickly fell under its spell, using the tune as an instrumental motif to link scenes. Three decades later, as "Mack the Knife," it would become a huge hit for Bobby Darin, Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald and others, albeit in a vastly watered-down translation – the "hero" of the original isn't a cute rat-pack gambler but a vicious thug, who at the end is asked his price for arranging the rape of a child. Its sanitized English version remains one of the most popular songs of the century.

Brecht's book and Weill's score sharpen the social criticism of Gay's original, but always with an intriguing but queasy unrest.

The Pabst movie: Lotte Lenya as Jenny, Rudolph Foerster as Mac |

After a weighty but sour and intentionally tedious overture and the "Moritat," the first act opens by saluting Peputsch with one of his original songs (the only direct quote from the Beggar's Opera) but its sweet melody is offset with gruff lyrics as Peachum rouses his army of beggars for another day's "work." At her wedding, lavishly celebrated amid food and d�cor stolen by Mac's henchmen, Polly dreams of murdering a whole town of men in the perversely catchy "Pirate Jenny" (chillingly sung by Judy Collins on her "In My Life" album). Tiger Brown, the police chief, drops in to recall with Mac, his former army buddy, the thrill of soldiering in the rousing but bitterly cynical and racist "Cannon Song" (when they encounter a fellow who's brown or yellow, they chop 'em up into beefsteak tartare). A bedraggled Polly explains to her horrified parents why nice men bore her in the teasingly sweet "Barbara-Song," Jenny laments the futility of wisdom in the waltzy "Solomon Song," Mrs. Peachum bemoans the lot of women in the docile "Ballad of Sexual Obsession," Mac and Jenny recall their blissful former life of pimping and whoring together in a lovely tango, and each act ends in pompous finales that seek to probe the deepest questions of humankind but arrive at far more earthy conclusions; the first one ends: "The world is poor and man's a shit / And that is all there is to it!" There are also some bizarre plot twists.

After Mac grooms Polly to oversee his "business" in his absence, she puts her training to good use as a bank president; as she puts it, why bother robbing one person when you can rob the whole public? Brown's daughter Lucy also falls for Mac and fights with Polly in a mock-dramatic duet.

The Lewis-Ruth Band |

To compel Brown to arrest his friend Mac, Peachum threatens to disrupt the Queen's coronation parade with an army of beggars. And at the end, the Queen herself not only sends a messenger to announce Mac's reprieve but rewards him with a peerage and a lifetime pension.

The premiere was sparsely attended, but word of this bizarre entertainment spread quickly. As George Martin noted with irony, the show treads a thin line, managing to keep audiences sufficiently amused while they remain to be insulted. According to Schebera, within the first year alone fifty theatres presented 4,000 performances, and record shops bulged with 40 recordings on 20 labels. By 1933, with translations made into 18 languages, Dreigroschenoper received the ultimate accolade for its challenging politics and music when the Nazis not only banned further performances but demanded that all scores be relinquished for destruction.

Theatre de Lys revival – 1954 MGM LP |

Weill himself became a prime target for Nazi cultural purification – accused of vilifying music through the dastardly crime of polluting German art with degenerate Negro rhythm, he and Lenya ultimately fled to America, where he would find a new career crafting socially-conscious Broadway shows.

While the War understandably dampened enthusiasm for German satire, the Threepenny Opera soon resurfaced. In 1952, Leonard Bernstein led a revival at Brandeis for which Marc Blitzstein fashioned an English adaptation. Moving to the 299-seat off-off-Broadway Theatre de Lys, it played to rave reviews for six years, featuring Lotte Lenya and a cast of then-unknowns (including Bea Arthur). The MGM cast recording LP sold a half-million copies. While the music is vibrant and colorful, the lyrics were tamed considerably for the recording – in the original tango, Mac relates how when a sailor appeared he would get out of Jenny's bed and have a beer while she earned her keep, but in the album version he gets up to pay the milkman while she is out working.

In 1976, Joseph Papp mounted a new production for the New York Shakespeare Festival that attempted to restore much of the original conception. In his album notes, Papp chided Blitzstein for vitiating the political and sexual thrust that gave the original its relentless power and for trying to make Brecht's thorny lyrics more singable by fitting them into conventional musical patterns rather than chafing them against the rhythm to make the audience listen more sharply.

1976 NY Shakespeare Festival LP |

The cast album, featuring Raoul Julia as Mac, boasts wonderfully vivid and characterful playing and singing and preserves the fine English adaptation by Ralph Manheim and John Willett that closely approaches the ultimate sting of Brecht's German.

Fortunately, we have lots of early recordings that provide a reliable guide to the highly unusual original performing style. The most renown and complete is a set of four Ultraphon 78s featuring 14 of the songs (albeit cut) by Lenya, Erich Ponto and Kurt Gerron of the original cast, the original arrangement for seven players (most of whom doubled - or tripled - on other instruments), the original Lewis-Ruth Band under Theo Mackeben, and introductory narration prepared by Brecht. The playing is lean and tough, the vocals pointed and intense (except for Willi Trenk-Trebitsch's perversely suave and detached Mac) and Lenya, as Polly, gets not only her own songs but "Pirate Jenny" that would become her anthem. The best CD transfer is on Teldec 42663.

The Ultraphon set was not made until December 1930. Arguably more authentic still are four songs cut in December 1928 by Harald Paulson, who created the role of Mac and who presents an intriguing range of styles – clipped notes suggesting routine recital for the "Moritat," lusty confidence for the "Cannon Song," rushed urgency for the "Ballad of Good Living," and fervent declamation for the first act finale. Carola Neher, the original Polly, cut "Pirate Jenny," "Barbara-Song" and a medley in May 1929, all more spoken than sung.

The Pabst movie: Polly presides over a meeting of her bank board |

Brecht himself, who loved to sing and had set many of his poems to his guitar accompaniment, recorded the "Moritat" and the "Song of the Insufficiency of Human Endeavor," also in May 1929, in a flat nasal bleating with ferociously rolled "R"s and farcically upbeat cabaret arrangements.

Although Weill reportedly dismissed as falsified arrangements all of these and the other many recordings, he excepted two irresistibly peppy instrumental excerpts (the tango and "Cannon Song") played in 1929 on an Odeon 78 by the Lewis-Ruth Band under Mackeben. In late 1928 he prepared his own arrangement for woodwinds of ten songs in seven movements, more thickly orchestrated but recorded in 1931 with great zest by the Berlin Staatsoper under Otto Klemperer, who had commissioned and led the premiere. (Klemperer's 1961 stereo EMI Philharmonia remake is far less spirited.)

Another primary source is a gritty 1931 movie by G. W. Pabst,

The Pabst movie: The final alliance |

shot in simultaneous German and French versions on the same sets with wholly different casts. While only the German format (featuring Lenya as Jenny, Neher as Polly and a viciously debonair Rudolph Foerster as Mac) is extant, four songs were issued from the French one ("l' Op�ra de Quat' Sous"), blandly sung but played with great spirit by the Lewis-Ruth Band under Mackeben. After selling the film rights, both authors sued – Brecht wanted to turn it into a Marxist manifesto (he lost) and Weill sought to prevent the use of outside music (he won, but the producers cut most of his songs anyway, using some only as background music). Authentic or not, it's a fascinating document, intensified by expressionist shot composition, garish lighting and nervous camera movements. Much of the remaining music was used more literally than ironically, as in the show – Mac and Polly's love ballad precedes their wedding rather than offsets their parting, Polly sings the "Barbara-Song" at her wedding to justify her love for Mac rather than to shock her parents, Jenny sings "Pirate Jenny" at the whorehouse to explain her betrayal of Mac (rather than Polly using it to strike a discordant key at her wedding), and the "Cannon Song" celebrates a final alliance among Police Chief Brown (power), arch-criminal Mac (brains), banker Polly (capital) and beggar-king Peachum (the masses) to consolidate their grip, both symbolic and literal, over London society. The ending, though, brings a chilling slap of social reality, turning abruptly from the laudatory merriment to a final shot of the truly downtrodden shuffling off into shadows, as a reprise of the "Moritat" rues that some dwell in darkness, others in light; you see those in brightness while the others drop from sight.

Among modern recordings, the Dreigroschenoper volume of Capriccio's 1997 Kurt Weill Edition (60 058) is deadly dull,  drained of any hint of style, but two stereo sets stand out. A lavishly documented 1958 Columbia album with Lenya (CBS 42367) strives for stylistic authenticity; although the deliberate pacing struggles to summon the work's full spirit, it's sung with great expressivity and in the three decades since her first recordings Lenya's voice had dropped an octave, replacing her former weirdly perverse shrill girly innocence with a world-weary wisdom. The avowed intent of a 1989 RIAS Berlin recording peopled with opera stars (London 430 075) was to restore Weill's music to preeminence while evading the "heightened and mannered speech" and "aggressive bellowing and whining" of the producers' conception of the prevailing accepted style. While the singing is full of character but without exaggerated inflection, the accompaniment is exquisitely detailed, often mining lodes of unsuspected splendor and beauty from the score (albeit at the cost of historical authenticity). The potential conflict between adhering to the original manuscript and respecting more recent emendations is finessed, as when "Pirate Jenny" is sung twice – once by Polly (as in the first stagings) and again by Jenny (after Weill shifted his show-stopper to his wife's role). drained of any hint of style, but two stereo sets stand out. A lavishly documented 1958 Columbia album with Lenya (CBS 42367) strives for stylistic authenticity; although the deliberate pacing struggles to summon the work's full spirit, it's sung with great expressivity and in the three decades since her first recordings Lenya's voice had dropped an octave, replacing her former weirdly perverse shrill girly innocence with a world-weary wisdom. The avowed intent of a 1989 RIAS Berlin recording peopled with opera stars (London 430 075) was to restore Weill's music to preeminence while evading the "heightened and mannered speech" and "aggressive bellowing and whining" of the producers' conception of the prevailing accepted style. While the singing is full of character but without exaggerated inflection, the accompaniment is exquisitely detailed, often mining lodes of unsuspected splendor and beauty from the score (albeit at the cost of historical authenticity). The potential conflict between adhering to the original manuscript and respecting more recent emendations is finessed, as when "Pirate Jenny" is sung twice – once by Polly (as in the first stagings) and again by Jenny (after Weill shifted his show-stopper to his wife's role).

The Threepenny Opera may evoke Berlin in the 1920s, but its cynical distrust of human endeavor, its frantic search for meaning amid moral chaos and its desparate anxiety for a more secure future are far more current than we might want to admit.

Copyright 2004 by Peter Gutmann

|