|

My late father-in-law and his siblings owned scrap metal yards. To reflect dawning social consciousness, in the 1970s they enhanced the respectability of their trade by rebranding their firm as a "conservator of natural resources." Recycling had become highly prized in business. In music, though, the trend was reversed.

Nowadays, with plagiarism easy to spot, no self-respecting musician would dare to intentionally pass off an old tune for an ostensibly new, original piece – other than through sampling or other deliberate tributes to respected forebears, although even that can have dire legal consequences. Indeed, with so much music out there, ever since the infamous "My Sweet Lord"/"He's So Fine" fiasco all composers run a significant risk of liability, even for subconsciously copying, or even sheer coincidence with, a prior published work. But in earlier times when publication was rare and delayed, copyright far less lucrative and infringement nearly impossible to prove, there was little danger and few qualms. With full impunity composers often wrote variations on others' tunes and were sorely tempted to squeeze maximum use out of killer themes of their own.

Franz Schubert (1797–1828) recycled three of his most beloved songs into instrumental pieces that would become even more celebrated than the originals.

|

![]() By the summer of 1819, Schubert had written dozens of major works from sonatas and quartets to masses and operas plus over 400 songs, yet not a single one had been published nor even performed in a public concert.

By the summer of 1819, Schubert had written dozens of major works from sonatas and quartets to masses and operas plus over 400 songs, yet not a single one had been published nor even performed in a public concert.

Schober's caricature of Vogl and Schubert in Steyr |

Paumgartner particularly liked one of Schubert's songs, "Die Forelle" ("The Trout"). Whether commissioned or intended as a "thank you" gift, Schubert used the song as the basis of an unusual quintet.  Some writers assert that Schubert wrote the work at Steyr and that he, Paumgartner and other local artists performed the new work there. Others, though, contend that Schubert wrote it upon his return to Vienna and sent it to Paumgartner, who struggled to perform it, as Schubert apparently had over-estimated his skill, and then shelved the precious work. (Due to Schubert's lifetime obscurity, biographical details tend to be sketchy.) Remarkably, Schubert produced no full autograph score; rather, in a prodigious feat reminiscent of Mozart, he appears to have directly written out the individual parts, from which a posthumous publication was assembled and issued in May 1829 both in original form (advertised as "a great Quintet for piano, violin, viola and double bass" – no mention of the cello part) and in a two-piano arrangement.

Some writers assert that Schubert wrote the work at Steyr and that he, Paumgartner and other local artists performed the new work there. Others, though, contend that Schubert wrote it upon his return to Vienna and sent it to Paumgartner, who struggled to perform it, as Schubert apparently had over-estimated his skill, and then shelved the precious work. (Due to Schubert's lifetime obscurity, biographical details tend to be sketchy.) Remarkably, Schubert produced no full autograph score; rather, in a prodigious feat reminiscent of Mozart, he appears to have directly written out the individual parts, from which a posthumous publication was assembled and issued in May 1829 both in original form (advertised as "a great Quintet for piano, violin, viola and double bass" – no mention of the cello part) and in a two-piano arrangement.

The vast majority of chamber music is written for standard combinations – sonatas for an instrument plus piano; trios for violin, cello and a viola or piano; and quartets for violin, viola, cello and a piano or second violin. An unconventional array of instruments suggests unusual circumstances or a customized purpose. (A famous, more modern example is the 1941 Quatour pour le fin de temps ("Quartet for the End of Time") for violin, cello, clarinet and piano, which Olivier Messiaen, a prisoner of war, wrote for himself and three other inmates.) Here, Schubert used the unusual combination of violin, viola, cello, double bass and piano (that is, substituting a string bass for the customary second violin). Scholars speculate as to why. Some assert that Paumgartner requested a companion piece to the only other quintet known to have used this grouping, written by Johann Hummel two decades before, the score of which Paumgartner may have had in his extensive library along with a collection of musical instruments.  Others suggest that Schubert wrote parts for the players who were available in Steyr. Yet others note that since Paumgartner was an amateur cellist Schubert added a bass to relieve his host from the cello's customary tedium of anchoring the bottom line in order to share in the melodies with which the work abounds. Aside from its unusual instrumental complement, Schubert's quintet has an uncommon five movements. Most commentators view the result as a hybrid between a formal chamber work and a serenade or divertimento that typically has a pleasant spirit, exceeds the usual four movements and comprises whatever instruments are on hand, and assert that it should be judged on that basis. (Indeed, Hummel's work was also published as an unconventionally-scored septet with flute, oboe and French horn but no violin.)

Others suggest that Schubert wrote parts for the players who were available in Steyr. Yet others note that since Paumgartner was an amateur cellist Schubert added a bass to relieve his host from the cello's customary tedium of anchoring the bottom line in order to share in the melodies with which the work abounds. Aside from its unusual instrumental complement, Schubert's quintet has an uncommon five movements. Most commentators view the result as a hybrid between a formal chamber work and a serenade or divertimento that typically has a pleasant spirit, exceeds the usual four movements and comprises whatever instruments are on hand, and assert that it should be judged on that basis. (Indeed, Hummel's work was also published as an unconventionally-scored septet with flute, oboe and French horn but no violin.)

Critical analysis aside, the quintet unmistakably bursts with the ecstatic good spirits behind its creation. "In it is enshrined the memory of a delightful summer of carefree leisure days � bathed in sunshine and the spirit of youth. � The threads of friendship, of human cordiality, of tenderness are woven into the very texture of the music" (Mila). The upbeat, collegial mood undoubtedly was magnified by the general escapist trend in Viennese music that favored the merriment of Rossini over the challenges of Beethoven (Stanley Finkelstein), Schubert's fond recollections of playing the viola in quartets with his father on cello and older brothers on violins; his relief at having recently escaped the drudgery of teaching after four years (Michael Griffel); his friends'willingness to provide for his needs in the absence of meaningful income; his reliance upon music to relieve the drabness of his everyday life (Paul Henry Lang); and, ironically, his lack of success that freed him to create music for the enjoyment of himself and his friends rather than for patrons or public (Lang).

![]() The song that inspired the "Trout" Quintet is based on a rather cute but trite 1783 poem by Christian Daniel Schubart (no relation to the composer) in which a trout joyously darts about in a clear brook to elude a fisherman, who finally, to the poet's ire, muddies the stream and catches the trout.

The song that inspired the "Trout" Quintet is based on a rather cute but trite 1783 poem by Christian Daniel Schubart (no relation to the composer) in which a trout joyously darts about in a clear brook to elude a fisherman, who finally, to the poet's ire, muddies the stream and catches the trout.

The opening of the "Trout" song |

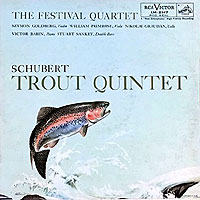

![]() Not only is the "Trout" Quintet one of the most popular of all chamber works (ranking # 1 in a 2005 WQXR listener survey), but it has consistently garnered universal scholarly praise while standing immune from adverse critique.

Not only is the "Trout" Quintet one of the most popular of all chamber works (ranking # 1 in a 2005 WQXR listener survey), but it has consistently garnered universal scholarly praise while standing immune from adverse critique.  While avoiding even the slightest hint of maudlin, it "perfectly captures a heartwarming state of mind" (Finkelstein), is "permeated by a delicious, infectious gaiety" and is "filled with lyrical, captivating melodies and gently persuasive humor" (Paul Myers) and "breathes the freshness of summer air in the Austrian Alps" (Robin Golding) – "music that is youth itself, � free and full of the natural solemnity of unspoiled idealism" (Lang) and that "inspires an affection that in human affairs we accord to our closest relations and to those friends from whose company we are never long absent" (William Mann). Attracting particular notice is the unusual instrumentation. Malcolm Rayment attributes the gap between the deep string bass and the higher registration of the rest of the ensemble to gypsy bands that Schubert heard while teaching in Hungary, which generally comprised the sonic extremes of violins and a bass, with only a cembalo in between. Mann notes that the string bass served to liberate from the tedious function of anchoring the harmony not only the cello but the piano as well, so that the left hand of the piano part dwells predominantly in the treble clef, adding an especial brilliance to its role. Finkelstein adds that the piano writing adheres to ordinary techniques of arpeggios, triplet figures, chromatic runs and octaves that might sound na�ve in other contexts but here, shorn of virtuoso fireworks, sounds just right.

While avoiding even the slightest hint of maudlin, it "perfectly captures a heartwarming state of mind" (Finkelstein), is "permeated by a delicious, infectious gaiety" and is "filled with lyrical, captivating melodies and gently persuasive humor" (Paul Myers) and "breathes the freshness of summer air in the Austrian Alps" (Robin Golding) – "music that is youth itself, � free and full of the natural solemnity of unspoiled idealism" (Lang) and that "inspires an affection that in human affairs we accord to our closest relations and to those friends from whose company we are never long absent" (William Mann). Attracting particular notice is the unusual instrumentation. Malcolm Rayment attributes the gap between the deep string bass and the higher registration of the rest of the ensemble to gypsy bands that Schubert heard while teaching in Hungary, which generally comprised the sonic extremes of violins and a bass, with only a cembalo in between. Mann notes that the string bass served to liberate from the tedious function of anchoring the harmony not only the cello but the piano as well, so that the left hand of the piano part dwells predominantly in the treble clef, adding an especial brilliance to its role. Finkelstein adds that the piano writing adheres to ordinary techniques of arpeggios, triplet figures, chromatic runs and octaves that might sound na�ve in other contexts but here, shorn of virtuoso fireworks, sounds just right.

Also frequently noted is structural simplification, which Joan Ashley credits with clinching the mood of a carefree holiday. Myers attributes the striking lack of development to the sheer overriding abundance of melody and the unusual form to Schubert's haste, while Hanspeter Krellmann lauds Schubert's conscious rejection of the turgid formality of classicism in favor of the principle of song. Yet the result is hardly primitive. Often cited are Schubert's audacious and abrupt key changes that intensify the harmonic interest with constant surprises; indeed, at the very outset he suddenly jumps in the 11th bar from A major to distant F major, which may seem jarring on paper but sounds utterly captivating.

The core of the work is the fourth of its five movements –

|

The opening of the fourth movement |

|

The openings of the allegro: ... andante: ... scherzo: ... and finale: |

While the variations movement is the centerpiece, the entire quintet is thoroughly delightful – breezy and beguiling, brimming with effortless melody and fascinating modulation, the instrumentation lending a rich and multi-colored blend of evolving sonority. Indeed, each of the unusual five (rather than four) movements is brilliantly inventive, but never ostentatiously so. (Henceforth, let's refer to the first movement as the allegro, the second as the andante, the third as the scherzo, the fourth as the variations and the fifth as the finale.) To cite just a few examples of Schubert's ingenuity: both the piano's opening figures and the vibrant scherzo theme teasingly hint at the song's memorable accompaniment that will emerge only at the end of the variations; the main theme of the first movement gestates only gradually from that same opening; developments are abridged or omitted altogether so as not to impede the flow or complicate the structures; recapitulations begin in the sub-dominant so as to wind up in the tonic without the need for elaborate bridge passages or new modulations; the finale is infused with faintly exotic Hungarian rhythms that Schubert presumably absorbed during his stay at the Esterhazys; and the finale plays a rollicking joke by seeming to end with a full cadence, only to plunge into a nearly literal recapitulation of the entire prior material. As Mann asserts, Schubert may have taken the lazy way out by simply repeating the first half of his marvelous finale with a minimal change of key but, after all, he was in a holiday mood, and in any event no one has ever complained!

![]() Schubert wrote of his own piano playing: "Several people have assured me that my fingers had transformed the keys into singing voices. If that is really true then I am delighted, since I cannot abide the damnable thumping that is peculiar to even the most distinguished pianists." Even keeping in mind that the pianofortes of Schubert's time spoke far more softly than the massive instruments of today, this provides significant guidance to evaluate efforts to realize his ideal even, as here, in a concerted work. Yet the "Trout" seemingly should also recognize the heady spirit of youthful innocence and the sheer joy of freedom amid the splendors of nature that lie at its very soul. The challenge faced by every performance and recording is to reconcile these potentially conflicting aims of lyricism and abandon.

Schubert wrote of his own piano playing: "Several people have assured me that my fingers had transformed the keys into singing voices. If that is really true then I am delighted, since I cannot abide the damnable thumping that is peculiar to even the most distinguished pianists." Even keeping in mind that the pianofortes of Schubert's time spoke far more softly than the massive instruments of today, this provides significant guidance to evaluate efforts to realize his ideal even, as here, in a concerted work. Yet the "Trout" seemingly should also recognize the heady spirit of youthful innocence and the sheer joy of freedom amid the splendors of nature that lie at its very soul. The challenge faced by every performance and recording is to reconcile these potentially conflicting aims of lyricism and abandon.

With that in mind �

- London String Quartet (John Pennington, Harry Waldo Warner, Charles Warwick Evans), Ethel Hobday (piano), Robert Cherwin (bass) (1928; Columbia 78s, CHARM download)

This first electrical "Trout" was a remake of the only prior set, a 1924 Columbia acoustic album with the same violist, cellist and pianist but James Levey on violin and Claude Hobday (Ethel's brother-in-law) on bass. Although Pennington only joined the London Quartet in 1927 (replacing Levey), Warner and Evans had been with the group since founding it in 1908. The juxtaposition of the intimate stylistic consistency of an established string quartet (minus its second violin) against the added perspective of outside guests on bass and especially piano became a frequent model for subsequent recordings. As might be expected, here the strings (discounting the bass, whose part rises above accompaniment only briefly in the third variation and in any event is far simpler) form a tight ensemble arising from their artistic association, offset by a somewhat freer piano (although Hobday was hardly a stranger to the London Quartet, with whom she had recorded the Schumann Quintet in 1917). The score specifies repeats of the first halves of the first and final movements; although omitted here, since these portions occupy the entire first and eighth 78 rpm sides they could have been programmed simply by playing each of those sides a second time before proceeding. (Even so, both movements comprise two virtually identical, albeit transposed, sections, and so repetitions of the first sections often are bypassed so as to minimize a feeling of redundancy.) The only other trims are the repeated first eight bars of each variation of the fourth movement (but not the "Trout" theme itself). The performance is rollicking, spirited and bright (at least until the variations, which seem just a bit stodgily paced after an especially propulsive scherzo). The fidelity is remarkably well-balanced and fully captures the richness of the bass anchor. Tempos are generally steady, other than a tendency to decelerate so as to emphasize transition points.

a 1924 Columbia acoustic album with the same violist, cellist and pianist but James Levey on violin and Claude Hobday (Ethel's brother-in-law) on bass. Although Pennington only joined the London Quartet in 1927 (replacing Levey), Warner and Evans had been with the group since founding it in 1908. The juxtaposition of the intimate stylistic consistency of an established string quartet (minus its second violin) against the added perspective of outside guests on bass and especially piano became a frequent model for subsequent recordings. As might be expected, here the strings (discounting the bass, whose part rises above accompaniment only briefly in the third variation and in any event is far simpler) form a tight ensemble arising from their artistic association, offset by a somewhat freer piano (although Hobday was hardly a stranger to the London Quartet, with whom she had recorded the Schumann Quintet in 1917). The score specifies repeats of the first halves of the first and final movements; although omitted here, since these portions occupy the entire first and eighth 78 rpm sides they could have been programmed simply by playing each of those sides a second time before proceeding. (Even so, both movements comprise two virtually identical, albeit transposed, sections, and so repetitions of the first sections often are bypassed so as to minimize a feeling of redundancy.) The only other trims are the repeated first eight bars of each variation of the fourth movement (but not the "Trout" theme itself). The performance is rollicking, spirited and bright (at least until the variations, which seem just a bit stodgily paced after an especially propulsive scherzo). The fidelity is remarkably well-balanced and fully captures the richness of the bass anchor. Tempos are generally steady, other than a tendency to decelerate so as to emphasize transition points.

- Ros� Quintet – Wolf Ros� (piano), Konrad Liebrecht (violin), Reinhard Wolf (viola), Kern Wolf (cello), Leberecht Goedecke (bass) (1928, Odeon 78s)

The Columbia electric set was cut in January 1928.  Remarkably, by June three more recordings had been made. April brought a rather perfunctory album by the so-called Ros� Quintet that, unlike the prolific London Quartet, may have been specially assembled for this project, as no other recordings seem to be extant from that entity (to be distinguished from the famed Ros� Quartet led by Arnold Ros�, the esteemed Viennese violinist and brother-in-law of Mahler) and indeed its members are barely known (none is even listed in the massive New Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians and all I could find for any of them was a smattering of discs by Reinhard Wolf and information that Konrad Liebrecht later became concert-master of the Honolulu Symphony Orchestra). The playing is rather crude and mechanical, but with considerable flexibility both in phrasing and overall tempos that adds a welcome degree of warmth, especially in the andante and variations. Inner voices are barely evident, often suggesting a sonata for violin and piano with occasionally audible accompaniment. All repeats are taken in the variations, but the entire second halves of both the andante and finale are omitted to fit each on a single side. (Suspicion of missing discs is dispelled by a December 1928 Gramophone ad that lists the set as having been issued in seven parts – two each for the allegro and the variations and one each for the andante, scherzo and finale; the Columbia album had nine sides – two for all movements but the scherzo.)

Remarkably, by June three more recordings had been made. April brought a rather perfunctory album by the so-called Ros� Quintet that, unlike the prolific London Quartet, may have been specially assembled for this project, as no other recordings seem to be extant from that entity (to be distinguished from the famed Ros� Quartet led by Arnold Ros�, the esteemed Viennese violinist and brother-in-law of Mahler) and indeed its members are barely known (none is even listed in the massive New Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians and all I could find for any of them was a smattering of discs by Reinhard Wolf and information that Konrad Liebrecht later became concert-master of the Honolulu Symphony Orchestra). The playing is rather crude and mechanical, but with considerable flexibility both in phrasing and overall tempos that adds a welcome degree of warmth, especially in the andante and variations. Inner voices are barely evident, often suggesting a sonata for violin and piano with occasionally audible accompaniment. All repeats are taken in the variations, but the entire second halves of both the andante and finale are omitted to fit each on a single side. (Suspicion of missing discs is dispelled by a December 1928 Gramophone ad that lists the set as having been issued in seven parts – two each for the allegro and the variations and one each for the andante, scherzo and finale; the Columbia album had nine sides – two for all movements but the scherzo.)

- International String Quartet (Andr� Mangeot, Frank Howard, Herbert Withers); Wilhelm Backhaus, piano; Charles Hobday, bass (1928, HMV 78s)

Of all the pianists on early Trout recordings Backhaus was the best known, both for his technical prowess and for helping to usher in the modern objective style with clean yet caring execution. Here, he plays in striking emotional synchronization with the strings, featuring subtly plastic tempos, sharp accents and wide dynamics to project a rather playful atmosphere. Alas, while the cello emerges when needed to carry its melody, the viola is all but obscured and the poor bass is barely heard when it should emerge to sing out the third variation. The scherzo and variations are played through without any repeats, presumably to fit them onto single sides and the entire work onto four discs, a marketing advantage, as all the others save the Ros� consumed at least one side of a fifth disc.

- Pro Arte Quartet (Alphonse Onnou, Germain Pr�vost, Robert Maas); Artur Schnabel, piano; Claude Hobday, bass (1935, HMV 78s)

After the flood of early electrical Trouts, including others by the Edith Lorand Quartet on Parlophone (1928) and the Gewandhaus Quartet on Polydor (1929), this next recording would be hailed as a classic. Famed for cutting the first (and, for many, still the preeminent) integral set of the Beethoven piano sonatas in the early 1930s – a monumental undertaking at the time – Schnabel also recorded pioneering sets of late Schubert sonatas, then barely known, to which he applied the same intellect and classicism. Schnabel's teacher, the great Theodor Leschetizky, who guided him toward Schubert, reportedly told him that he would never be a great pianist because he was a musician and indeed Schnabel, himself a modernist composer, probed and conveyed the essential structure of the works he performed. Not a great technician, Schnabel's recordings are replete with lapses, including some blurring of rapid figurations here, but they add a deeply human touch and are easily forgiven. The Belgian Pro Arte's versatility ranged from its extensive sets of 27 Haydn quartets through Milhaud and Bartok, but here they complement Schnabel's cerebral approach with a magnificent reading that treads a fine balance between discipline and indulgence – never overly effusive yet never dull. Committed and persuasive, yet shorn of extraneous interpretive personality, it remains cherished as a high point of chamber music on record and serves as a paradigm for all the Trouts that would follow.

including others by the Edith Lorand Quartet on Parlophone (1928) and the Gewandhaus Quartet on Polydor (1929), this next recording would be hailed as a classic. Famed for cutting the first (and, for many, still the preeminent) integral set of the Beethoven piano sonatas in the early 1930s – a monumental undertaking at the time – Schnabel also recorded pioneering sets of late Schubert sonatas, then barely known, to which he applied the same intellect and classicism. Schnabel's teacher, the great Theodor Leschetizky, who guided him toward Schubert, reportedly told him that he would never be a great pianist because he was a musician and indeed Schnabel, himself a modernist composer, probed and conveyed the essential structure of the works he performed. Not a great technician, Schnabel's recordings are replete with lapses, including some blurring of rapid figurations here, but they add a deeply human touch and are easily forgiven. The Belgian Pro Arte's versatility ranged from its extensive sets of 27 Haydn quartets through Milhaud and Bartok, but here they complement Schnabel's cerebral approach with a magnificent reading that treads a fine balance between discipline and indulgence – never overly effusive yet never dull. Committed and persuasive, yet shorn of extraneous interpretive personality, it remains cherished as a high point of chamber music on record and serves as a paradigm for all the Trouts that would follow.

- Ney Trio (Elly Ney, piano; Max Straub, violin; Ludwig Hoelscher, cello), Walter Trampler, viola; Herman Schubert, bass (1938, Electrola 78s)

Nowadays Ney's ardent embrace of the Nazis and her personal esteem for Hitler largely eclipses her musical reputation.  Yet her playing was vaunted for spirituality and spontaneity, amply displayed in her 1936 recording of Beethoven's final sonata. All the more surprising, then, that her Trout [also issued in the name of the Straub Quartet] emerges as fleet, uninflected and altogether modern in its approach and clear, crisply accented and overall bright in its sound. The variations, in particular, manage to be fully characterized while never losing a sense of natural flow and internal logic – and never even hint at deep currents beneath the gently rippling surface. Altogether it's a brilliant rendition that, more than any other of its vintage (i.e., the Stross Quartet with Franz Rupp on Telefunken [1937] – somewhat ironically, Wilhelm Stross was an original member of the Ney Trio]), points the way to more recent views of the work.

Yet her playing was vaunted for spirituality and spontaneity, amply displayed in her 1936 recording of Beethoven's final sonata. All the more surprising, then, that her Trout [also issued in the name of the Straub Quartet] emerges as fleet, uninflected and altogether modern in its approach and clear, crisply accented and overall bright in its sound. The variations, in particular, manage to be fully characterized while never losing a sense of natural flow and internal logic – and never even hint at deep currents beneath the gently rippling surface. Altogether it's a brilliant rendition that, more than any other of its vintage (i.e., the Stross Quartet with Franz Rupp on Telefunken [1937] – somewhat ironically, Wilhelm Stross was an original member of the Ney Trio]), points the way to more recent views of the work.

- Budapest Quartet (Josef Roisman, Boris Kroyt, Mischa Schneider); Mieczyslaw Horszowski, piano; Georges Moleux, bass (1949, Columbia LP)

Skipping ahead over another half-dozen Trouts we arrive at the Budapest, arguably the most acclaimed and popular quartet of its time, then (amid shifting personnel) comprised of Russian-born Americans. The sheer beauty of their deep sonority arises in part from playing a set of Stradivarious instruments in the Library of Congress where the Budapest Quartet was in residence, and yet the result is vibrant, with exquisite balances, finely-shaped phrases and fully-synchronized attacks.  Horszowski shared Schnabel's straight-forward, intellectual outlook and was acclaimed as an ideal chamber partner throughout his extraordinarily long career (he was still giving recitals at age 99!). Here he accommodates and furthers the strings' fundamentally relaxed yet constantly attentive approach. A live Budapest Quartet performance with George Szell at the keyboard, recorded at the Library in 1946 (Bridge CD), is just as accomplished and with a more swaggering scherzo and assertive finale, but rather thin sound. The Budapest recut a stereo Trout in 1963 again with Horszowski (but Julius Levine on bass).

Horszowski shared Schnabel's straight-forward, intellectual outlook and was acclaimed as an ideal chamber partner throughout his extraordinarily long career (he was still giving recitals at age 99!). Here he accommodates and furthers the strings' fundamentally relaxed yet constantly attentive approach. A live Budapest Quartet performance with George Szell at the keyboard, recorded at the Library in 1946 (Bridge CD), is just as accomplished and with a more swaggering scherzo and assertive finale, but rather thin sound. The Budapest recut a stereo Trout in 1963 again with Horszowski (but Julius Levine on bass).

- Academy of Ancient Music Chamber Ensemble (Simon Standage, Trevor Jones, David Watkin); Steven Lubin, fortepiano; Amanda MacNamara, bass (1980, Oiseau-Lyre CD)

- Hausmusik (Monica Huggett, Roger Chase, Richard Lester), Cyril Huv�, piano; Chi-Chi Nwanoku, bass (1991, EMI Reflexe CD)

Although the historically-informed performance movement focused mainly on the orchestral repertoire (in which the older wind and brass timbres are most evident), original instrument ensembles also sought to replicate the sound of early Romantic chamber works. While the lower pitch, gut strings and infrequent vibrato in use at the time seem only slightly different from modern string sound, they do offer a more subtle texture when combined with the wooden frames, low string tension and leather hammers of early fortepianos. Of these two accounts, the Hausmusik is somewhat more leisurely and is joined on its CD with the Hummel quintet that may have inspired Paumgartner and/or Schubert.

A cautionary note about stereo Trouts: most include the repeat of the entire opening half of the allegro and a few add the repeat of the finale as well.

As a result, these sections may seem too long and repetitive for modern taste, since both movements already comprise two virtually identical halves, and so taking the repeats creates yet third parallel sections that tend to stretch the material thin and push the overall length of this modestly-proportioned work beyond 40 minutes. In any event, nowadays we can easily create our own full versions on CD if we want by simply returning to the beginning of the allegro and finale at their mid-points, a button-push luxury inconceivable to Schubert and his hoped-for audiences, who undoubtedly would have welcomed an opportunity to revel in repeats of the recurring portions of a work that they were unlikely to ever have the opportunity to hear again.

As a result, these sections may seem too long and repetitive for modern taste, since both movements already comprise two virtually identical halves, and so taking the repeats creates yet third parallel sections that tend to stretch the material thin and push the overall length of this modestly-proportioned work beyond 40 minutes. In any event, nowadays we can easily create our own full versions on CD if we want by simply returning to the beginning of the allegro and finale at their mid-points, a button-push luxury inconceivable to Schubert and his hoped-for audiences, who undoubtedly would have welcomed an opportunity to revel in repeats of the recurring portions of a work that they were unlikely to ever have the opportunity to hear again.

Stereo Trouts which I enjoy: Borodin Quartet/Sviatoslav Richter (1963, EMI – for an exquisitely sensitive piano part that the strings fully support), Peter Serkin/Alexander Schneider/Michael Tree/David Soyer/Julius Levine (1965, Vanguard – both for the 18-year old pianist's sheer sense of youthful joy and the fanciful cover), Melos Ensemble/Lamar Crowson (1967, Angel/EMI – especially elegant), Marlboro/Rudolf Serkin (1967, Columbia), Cleveland Quartet/Alfred Brendel (1977, Philips), Smetana Quartet/Jan Panenka (1977, Supraphon – elegant), Takasz Quartet/Zolt�n Kocsis (1982, Hungaroton – with all repeats, but fast!), Alban Berg Quartet/Elizabeth Leonskaja (1986, EMI), Kodaly Quartet/Jen� Jand� (1992, Naxos) and James Levine/Gerhart Hetzel/Alois Posch/Wolfram Christ/Georg Faust (1997, DG – with vivid inflection and response to the shifting moods).

|

![]() Only five years later, illness and poverty had plunged Schubert to the nadir of his brief life and to the extreme opposite end of his emotional spectrum.

In late 1822, he had contracted syphilis and spent most of the next year confined and weakened by pain and debilitating (albeit ineffectual) treatments. Without the necessary personal attention, his career stalled and income ceased. Even when he emerged from the first two phases of his illness,

Only five years later, illness and poverty had plunged Schubert to the nadir of his brief life and to the extreme opposite end of his emotional spectrum.

In late 1822, he had contracted syphilis and spent most of the next year confined and weakened by pain and debilitating (albeit ineffectual) treatments. Without the necessary personal attention, his career stalled and income ceased. Even when he emerged from the first two phases of his illness,

Schubert in 1821 Sketch by Leopold Kupelweiser |

Most composers either sublimated their extreme personal mood swings into a rarified idealism or refined their work over a sufficiently long time to temper their soaring inspirational peaks and plunging fits of despair.

16th century depictions of "Death and the Maiden" by Sebald Behem and Hans Baldung |

![]() For his 14th quartet, Schubert reached back to a remarkably concise and chilling song he had written in his teens to an eight-line poem by Matthius Claudius, Der Tod und das M�dchen ("Death and the Maiden"), in which a girl begs to be let alone by death, who soothes her with a promise of friendship and gentle sleep. The concept was hardly novel – the ancient view of death was as a friend offering eternal rest and, beginning in the early 16th century, artists seized upon the medieval trope of a symbolic contrast between nubile girls and gnarly figures of decay, together with the many overtones of ripe beauty vs. rotting age, vitality vs. stasis, radiance vs. gloom and, of course, life vs. death. Like ancient prayers and haiku, its simplicity is deceptive, leaving much to be inferred beyond the extreme brevity:

For his 14th quartet, Schubert reached back to a remarkably concise and chilling song he had written in his teens to an eight-line poem by Matthius Claudius, Der Tod und das M�dchen ("Death and the Maiden"), in which a girl begs to be let alone by death, who soothes her with a promise of friendship and gentle sleep. The concept was hardly novel – the ancient view of death was as a friend offering eternal rest and, beginning in the early 16th century, artists seized upon the medieval trope of a symbolic contrast between nubile girls and gnarly figures of decay, together with the many overtones of ripe beauty vs. rotting age, vitality vs. stasis, radiance vs. gloom and, of course, life vs. death. Like ancient prayers and haiku, its simplicity is deceptive, leaving much to be inferred beyond the extreme brevity:

|

Das M�dchen: Vor�ber! Ach vor�ber! Geh wilder Knochenmann! Ich bin noch jung, geh Lieber! Und r�hre mich nicht an. Der Tod: Gib deine Hand, du sch�n und zart Gebild! Bin Freund, und komme nicht, zu strafen: Sei gutes Muts! ich bin nicht wild, Sollst sanft in meinen Armen schlafen. |

The Maiden: It is over! Oh, it is over! Go, wild man of bone! I am still young, go my dear! And do not touch me. Death: Give me your hand, you lovely and tender thing! I am a friend, and do not come to punish. Be of good cheer! I am not wild, Gently in my arms you will sleep. |

In full keeping with the text, Schubert's setting is unnerving in its disciplined D-minor minimalism.

The opening of the "Death and the Maiden" song |

The vast majority of recordings take the song far too slowly at a funereal pace that improperly projects profound personal grief rather than the inference of Schubert's moderate tempo that death is a mere routine shorn of emotion. Interestingly, only a month later Schubert provided a far more conventionally melodic setting for Joseph von Spaun's "Der J�ngling und der Tod" ("The Young Man and Death") in which death truly is a friend, taking pity on a young man who yearns to be led from the world's miseries into the land of dreams, a remarkable foretaste of the wish in that March 1824 letter which Schubert would write from the depths of his own depression.

The vast majority of recordings take the song far too slowly at a funereal pace that improperly projects profound personal grief rather than the inference of Schubert's moderate tempo that death is a mere routine shorn of emotion. Interestingly, only a month later Schubert provided a far more conventionally melodic setting for Joseph von Spaun's "Der J�ngling und der Tod" ("The Young Man and Death") in which death truly is a friend, taking pity on a young man who yearns to be led from the world's miseries into the land of dreams, a remarkable foretaste of the wish in that March 1824 letter which Schubert would write from the depths of his own depression.

![]() Schubert had felt his way through eleven early quartets. His first, at age 13, was written in various keys, a heady fusion of inexperience and bold venturing. In 1820 he produced a single mature quartet movement in C minor, discovered only posthumously and now called the "Quartettsatz," an emotional precipice in which barely persuasive contemplation is constantly undermined by a recurrent aggressive storm. As with his similarly brash 1822 "Unfinished" Symphony, debate swirls as to whether he abandoned the "Quartettsatz" (as is suggested by a tentative sketch for a second movement) or intended it to stand by itself.

Schubert had felt his way through eleven early quartets. His first, at age 13, was written in various keys, a heady fusion of inexperience and bold venturing. In 1820 he produced a single mature quartet movement in C minor, discovered only posthumously and now called the "Quartettsatz," an emotional precipice in which barely persuasive contemplation is constantly undermined by a recurrent aggressive storm. As with his similarly brash 1822 "Unfinished" Symphony, debate swirls as to whether he abandoned the "Quartettsatz" (as is suggested by a tentative sketch for a second movement) or intended it to stand by itself.

On January 31, 1824 Schubert met Ignaz Schuppanzigh, Beethoven's close friend and teacher who was introducing Beethoven's final works, and wrote for him a quartet in A minor (now generally numbered as Schubert's 13th quartet, and known as the "Rosamunde") that Schuppanzigh's ensemble performed on March 14, was well-received, and then was published. Significantly, the title page announced (and dedicated to Schuppanzigh) three quartets. Presumably, the Rosamunde was the first of the three to which Schubert referred. The second would have been the "Death and the Maiden" quartet in D minor (# 14), of which the autograph copy is dated March 1824. Alas, Schuppanzigh was far less pleased with it and reportedly advised Schubert to stick to writing songs. (Understandably stung, Schubert either altogether abandoned the final quartet of his planned triumvirate, or perhaps deferred those plans until June 1826 when he wrote his final quartet in G Major, now designated as his # 15.) As for the D minor quartet, during Schubert's life it was performed only privately in early 1826 (when Schubert revised the score and abridged the first movement) and then was rejected by his publisher.

and known as the "Rosamunde") that Schuppanzigh's ensemble performed on March 14, was well-received, and then was published. Significantly, the title page announced (and dedicated to Schuppanzigh) three quartets. Presumably, the Rosamunde was the first of the three to which Schubert referred. The second would have been the "Death and the Maiden" quartet in D minor (# 14), of which the autograph copy is dated March 1824. Alas, Schuppanzigh was far less pleased with it and reportedly advised Schubert to stick to writing songs. (Understandably stung, Schubert either altogether abandoned the final quartet of his planned triumvirate, or perhaps deferred those plans until June 1826 when he wrote his final quartet in G Major, now designated as his # 15.) As for the D minor quartet, during Schubert's life it was performed only privately in early 1826 (when Schubert revised the score and abridged the first movement) and then was rejected by his publisher.

Schubert's March 31, 1824 letter provides significant insights beyond his psychic state. He wrote: "I have composed two quartets � and intend to write another. ... In this way I intend to pave the way toward the grand symphony."  Whether this refers to his future "Great" C Major symphony, it seems to herald that large-scale drama would characterize his new quartets. And after referring to news that Beethoven was about to give his now-famous colossal concert that would introduce his "Choral" Symphony, Consecration of the House Overture and three movements of his Missa Solemnis, Schubert added: "God willing, I am also thinking of giving a similar concert in the next year." Thus, despite his dire situation, Schubert's ambitions still soared.

Whether this refers to his future "Great" C Major symphony, it seems to herald that large-scale drama would characterize his new quartets. And after referring to news that Beethoven was about to give his now-famous colossal concert that would introduce his "Choral" Symphony, Consecration of the House Overture and three movements of his Missa Solemnis, Schubert added: "God willing, I am also thinking of giving a similar concert in the next year." Thus, despite his dire situation, Schubert's ambitions still soared.

Several commentators reject any but a purely musical link between the "Death and the Maiden" song and the A-minor quartet. Thus Douglas Townsend scorns Schubert's preoccupation with death as a fanciful story – "one of those romantic misconceptions which make good copy and movie scenarios but have nothing to do with reality." Rather, they point to the theme's chorale structure and its lack of rhythmic and melodic interest that made it an ideal subject for variation treatment and contend that Schubert appropriated it on that basis alone. Some go further to observe that the vocal lines of Schubert's songs typically do not depend upon the text but rather provide suitable but unspecific musical support and thus are readily adapted for instrumental-only purposes regardless of the original literary associations. Others take a middle ground, positing that the quartet merely reflected Schubert's overall state of mind and contrasting moods (Homer Ulrich) or that the musical ideas first suggested by the poem held further possibilities to explore in other media and contexts (Jennifer Standage). Yet given Schubert's dire circumstances and extreme depression at the time, it hardly seems implausible that the morbid subject of his earlier song assumed an acutely personal import. Indeed, to a far greater degree than in the "Trout," the various moods invoked by the song seem to pervade the quartet.

![]() The heart of the quartet is its second movement,

The heart of the quartet is its second movement,

The opening of the second movement (andante) |

The remainder of the quartet provides a fine prologue and aftermath for this central drama, establishing and sustaining the mood through persistent minor tonality (the first quartet to be written with all movements so cast), tense rhythms, bold harmonic progressions and stormy emotion – even more extreme than in any of Beethoven's quartets.

The unforgettable opening of the allegro

The opening of the first movement (allegro) |

The scherzo is a grotesque dance of death in D minor, sharp and offbeat, with gruff allure, only briefly mellowed by a trio in D Major before lapsing back.

|

The opening theme of the scherzo |

The finale is a tarantella, a frenzied 6/8 presto dance to stave off death, all coiled tension and bundled triplet energy that persists even through nominally contrasting portions, culminating in a vertiginous acceleration to a breathless and violent prestissimo (= as fast as possible), "manic exuberance � spinning out of control toward a vortex of doom" (Donat) – we all know that the destiny of humanity ultimately is to lose the battle against mortality, but Schubert seemingly urges us (and himself, of course) to use our last drop of energy to resist.

|

The opening theme of the finale |

![]() The contemporaneous "Rosamunde" Quartet in A minor (# 13) provides a fascinating psychological companion piece. Despite occasional moderate outbursts, the overall mood is of grace and submission; even the scherzo is restrained and tentative. The theme of the andante is a rather bland and gentle tune from an Entr'acte from Schubert's incidental music for the play Rosamunde that occurs at the decisive point where a princess resolves to return to her bucolic childhood home. Indeed, the overall lightness of the music harks back to the pleasant diversions of Schubert's own early student pieces.

The contemporaneous "Rosamunde" Quartet in A minor (# 13) provides a fascinating psychological companion piece. Despite occasional moderate outbursts, the overall mood is of grace and submission; even the scherzo is restrained and tentative. The theme of the andante is a rather bland and gentle tune from an Entr'acte from Schubert's incidental music for the play Rosamunde that occurs at the decisive point where a princess resolves to return to her bucolic childhood home. Indeed, the overall lightness of the music harks back to the pleasant diversions of Schubert's own early student pieces.

The "Rosamunde" Quartet suggests that Schubert, too, while pining for his happier past, might accept his fate and hide from the future, but it's the anger and drive of the "Death and the Maiden" Quartet that decisively opens the door to Schubert's mature style.

The "Rosamunde" Quartet suggests that Schubert, too, while pining for his happier past, might accept his fate and hide from the future, but it's the anger and drive of the "Death and the Maiden" Quartet that decisively opens the door to Schubert's mature style.

Curiously, Felix Mendelssohn, known in his time as a highly perceptive and influential critic, dismissed the Death and the Maiden quartet as "nasty music" and, citing its incessant harmonic modulation, slighted it for faulty structure. Cecilia Porter attributes this to Schubert's resourceful gift for fantasy in which harmonic and structural surprises give an impression of being extemporized (and thus frustrates conventional scholarly expectation and analysis). Subsequent critics have universally praised it on a variety of grounds, especially as a bridge between two musical eras. Thus Lang hails it as "a triumph of the reconciliation of classicism and romanticism" in which "force generates form – a force that makes itself felt in the smallest particle of a composition, giving it the unity of classicism" – that is, the equilibrium between form and content that defines classicism. Yet Jaroslav Holecek hails it as "the perfect incarnation of the spirit of Romanticism – an utterly subjective work filled with profoundly-felt sorrow in varying degrees of intensity." Simon attempts to reconcile these views by recognizing it as "the most spiritually unified and inspired of all Schubert's chamber music" while emphasizing its progressive experimentation with cross-rhythms and unconventional but highly dramatic chord progressions.

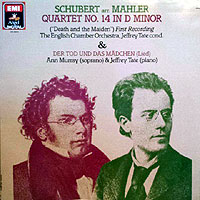

Two derivative works are worth noting. First, the quartet has been orchestrated, at first by Gustav Mahler, who programmed the Andante in 1894 and peppered the rest of his copy of the score with extensive annotations that others have realized. While we tend to sneer at such efforts nowadays, they once were rampant, including such seemingly sacrosanct works as Bach organ pieces (which even the purist Toscanini performed in syrupy full orchestrations) and Beethoven's Hammerklavier Piano Sonata (dressed in full instrumentation by Felix Weingartner, who also was known for adhering to the fidelity of [most] scores). While our modern notions of integrity regard such efforts as misguided, they served a valuable function by exposing concert audiences to works they might otherwise have shunned.

Other than thickening the texture with added bass and octave doublings, Mahler left Schubert's work largely intact. Even so, something clearly is lost – the sheer sense of exertion of coaxing transcendent feeling out of a mere four instruments (or, for the Bach and Beethoven, a single keyboard). All great art deepens its impact by drawing us into the process of creating meaning from an efficient deployment of limited resources. Here, while the textures of the Andante tend to survive Mahler's enrichment, in the rest we are deprived of the personal communication from a mere handful of instruments that induces us to participate in the creative process and thereby to derive a totality of the musical experience.

Other than thickening the texture with added bass and octave doublings, Mahler left Schubert's work largely intact. Even so, something clearly is lost – the sheer sense of exertion of coaxing transcendent feeling out of a mere four instruments (or, for the Bach and Beethoven, a single keyboard). All great art deepens its impact by drawing us into the process of creating meaning from an efficient deployment of limited resources. Here, while the textures of the Andante tend to survive Mahler's enrichment, in the rest we are deprived of the personal communication from a mere handful of instruments that induces us to participate in the creative process and thereby to derive a totality of the musical experience.

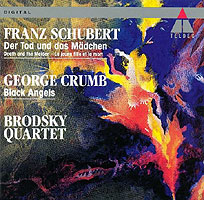

Far more relevant to our times is George Crumb's 1970 Black Angels, a haunting modern masterpiece for amplified string quartet, percussion and voices whose intensely theatrical contrasts, disparate materials and innovative textures and techniques reflect the moral agony of the Vietnam War. Indeed it just could be the most extraordinary work of art to have emerged from that painful chapter of history. Of its 13 brief sections, one directly quotes the Andante of the Schubert and others evoke it beneath mantles of fresh perspectives. Indeed, the entire work seems to summon and link us to Schubert's conception indirectly, as by launching the opening "Night of the Electric Insects" with a truly shocking sound of piercing, earsplitting, distorted, screaming violins that jolts modern listeners with a full equivalency of the startling opening of the original that would have so shaken an audience of Schubert's time (had there been any). Its first recording by the Kronos Quartet (in an eclectic recital on a Nonesuch CD) bristles with energy. Somewhat broader yet still potent readings of both the Schubert and Crumb pieces by the Brodsky Quartet share a 1993 Teldec CD. We can only wonder whether Schubert would have been appalled or flattered at Crumb's bold recyling of his own recycled work.

![]() As a tribute of sorts to the profound taste of classical music fans, a review of catalogs produced over several decades documents that the dark Death and the Maiden consistently has boasted twice as many recordings as any of Schubert's other, far more lyrical and outwardly "enjoyable" quartets. My ideal performance would combine Schubert's innate lyricism with the work's inherent drama and emotional depth while respecting the sublimation that art requires.

As a tribute of sorts to the profound taste of classical music fans, a review of catalogs produced over several decades documents that the dark Death and the Maiden consistently has boasted twice as many recordings as any of Schubert's other, far more lyrical and outwardly "enjoyable" quartets. My ideal performance would combine Schubert's innate lyricism with the work's inherent drama and emotional depth while respecting the sublimation that art requires.

- London String Quartet (1925, Columbia 78s)

As with their Trout Quintet, the London String Quartet boasts the earliest extant recording of a complete Death and the Maiden (labelled at the time as Schubert's quartet # 6).

The World Encyclopedia of Recorded Music lists single movements (each on two sides) by the Philharmonic (finale, 1915), Flonzaley (allegro, 1924) and Lener (andante, 1925) string quartets. We should also note that Frank Forman's remarkably detailed Acoustic Chamber Music Sets refers to a complete 1925 set by the Edith Lorand Quartet and, intriguingly, another by the Leo Abkov Quartet on the World Records label using an experimental long–play technology that relied upon constant groove velocity (as with CDs) rather than constant angular velocity (as with vinyl), such that the disc began to rotate slowly and then increased speed as the needle approached the center. Although theoretically efficient (each disc contained the equivalent of three 78s), precise speed control proved too complex for commercial success. In any event, the London Quartet was by far the most prolific and eclectic chamber group of its time on records (Forman lists 24 complete acoustic sets ranging from Haydn to Elgar) and its early electrical album of the Schubert amply upholds its reputation and is as fine as one could hope for an introduction to the work, with enthusiastic playing (albeit with some dicey violin intonation in the andante), attentive ensemble, strong accents, careful balances and relatively wide dynamics, all captured in remarkably fine fidelity. To fit the andante onto two sides (of a total of eight), a funereal tempo is avoided and all repeats are omitted.

The World Encyclopedia of Recorded Music lists single movements (each on two sides) by the Philharmonic (finale, 1915), Flonzaley (allegro, 1924) and Lener (andante, 1925) string quartets. We should also note that Frank Forman's remarkably detailed Acoustic Chamber Music Sets refers to a complete 1925 set by the Edith Lorand Quartet and, intriguingly, another by the Leo Abkov Quartet on the World Records label using an experimental long–play technology that relied upon constant groove velocity (as with CDs) rather than constant angular velocity (as with vinyl), such that the disc began to rotate slowly and then increased speed as the needle approached the center. Although theoretically efficient (each disc contained the equivalent of three 78s), precise speed control proved too complex for commercial success. In any event, the London Quartet was by far the most prolific and eclectic chamber group of its time on records (Forman lists 24 complete acoustic sets ranging from Haydn to Elgar) and its early electrical album of the Schubert amply upholds its reputation and is as fine as one could hope for an introduction to the work, with enthusiastic playing (albeit with some dicey violin intonation in the andante), attentive ensemble, strong accents, careful balances and relatively wide dynamics, all captured in remarkably fine fidelity. To fit the andante onto two sides (of a total of eight), a funereal tempo is avoided and all repeats are omitted.

- Budapest Quartet (1927, HMV)

Despite bearing the same name and maintaining a certain commercial and institutional continuity, the Budapest Quartet of 1927 had entirely different personnel than the 1950 group that would record the Trout (and re–record the Death and the Maiden). Before assuming its Russian–born American complexion in the 1930s, at the time of their 1927 recording the Budapest comprised its founders Emil Hauser (first violin), Istvan Ipolyi (viola) and Harry Son (cello) plus Imre Pogany (second violin) – all Hungarian except for Son, who was Dutch. The Budapest's 1954 Columbia recording (with Joseph Roisman and Jac Gorodetzky, violins; Boris Kroyt, viola; and Mischa Schneider, cello) is fundamentally similar but somewhat more overtly dramatic and seems to project a greater differentiation of textures, although largely obscured by its boxy sound (at least on the original LP). In contrast, the earlier version has a more uniform sonority and retains the Old World artifact of frequent, although largely tasteful portamento (sliding between notes), yet also manages to project heartfelt involvement, avoiding any sense of an abstract translation of the score into sound.

- Capet Quartet (1928, Columbia)

As summarized by string authority Tully Potter,

Lucien Capet was known for his 19th century mannerisms with minimal vibrato (thus placing extreme emphasis on exposed intonation), a pure, homogenous sound, transparent chords and a delicate rhythmic pulse. Capet was especially hailed as an acknowledged master of bowing control and technique, on which he wrote a treatise. A chamber musician throughout his life, he cut the Death and the Maiden during his final (55th) year with the last of the five quartets he led (comprising Maurice Hewett, Henri Benoit and Camille Delobelle). The allegro plows boldly ahead with burning urgency (about two minutes faster than the London or Budapest) and only the subtlest rhythmic variation, lending a sense of unrestrained impetus and inevitability in lieu of the others' pauses to outline the structure. Swift tempos and omitted repeats aside, perhaps the Capet's comes the closest of any recording to preserving an authentic Romantic quartet style. (A 1937 set by the other preeminent French quartet, the confusingly-named Calvert (Telefunken), is rather bland by comparison.)

Lucien Capet was known for his 19th century mannerisms with minimal vibrato (thus placing extreme emphasis on exposed intonation), a pure, homogenous sound, transparent chords and a delicate rhythmic pulse. Capet was especially hailed as an acknowledged master of bowing control and technique, on which he wrote a treatise. A chamber musician throughout his life, he cut the Death and the Maiden during his final (55th) year with the last of the five quartets he led (comprising Maurice Hewett, Henri Benoit and Camille Delobelle). The allegro plows boldly ahead with burning urgency (about two minutes faster than the London or Budapest) and only the subtlest rhythmic variation, lending a sense of unrestrained impetus and inevitability in lieu of the others' pauses to outline the structure. Swift tempos and omitted repeats aside, perhaps the Capet's comes the closest of any recording to preserving an authentic Romantic quartet style. (A 1937 set by the other preeminent French quartet, the confusingly-named Calvert (Telefunken), is rather bland by comparison.)

- Kolisch Quartet [scherzo only] (1934, Columbia)

Schubert's quartet was meant to be experienced as a whole, and so I've restricted myself to complete recordings. Yet this single side, the most deeply personal imaginable, just can't be ignored. Rudolf Kolisch was a student of Schoenberg and devoted himself to modern chamber music but commercially recorded mostly Mozart and Schubert. Perhaps as a reflection of the volatility of his approach, his eponymous quartet changed personnel an astounding 20 times during its 24-year existence. Perhaps to foster intensely individualized readings, they played entirely from memory. Of Death and the Maiden they cut only the scherzo, in which a saccharine trio seems a caricature of Viennese style by oozing among the notes with exaggerated scoops, vibrato and rhythmic distension and is sandwiched between ferociously intense opening and concluding sections replete with their own warped inflations. Utterly unique if not downright shocking! What a shame they didn't wax the rest, although, judging from their other vibrant but more conventional Schubert (the full Rosamunde and G-major quartets, plus the Trout variations movement), it might have been far more idiomatic.

- Busch Quartet (1936, HMV)

Although a "pure" Aryan,

Adolph Busch was an early and fervent foe of Nazism and after 1933 refused to play in his own country where he was best known, serving instead through recitals and recordings as an ambassador to the rest of the world of Bach, Beethoven, Brahms and other cornerstones of German musical culture. Often acclaimed as the finest of all Death and the Maidens, this 1936 recording (with G�sta Andreasson, Karl Doktor and Adolf's younger brother Hermann) still overwhelms with its ideal blend of intense musicality and innate spirituality in which everything just sounds so "right." Every detail is heartfelt and impresses with its utter sincerity while preserving the musical continuity, never wresting attention from the music itself – technique as the servant of art. Phrasing, transitions, balances and inflection are smooth yet vividly characterized. All four players seem a single, perfectly-attuned instrument that exemplifies the old saying that a good quartet plays together while a great quartet breathes together.

Adolph Busch was an early and fervent foe of Nazism and after 1933 refused to play in his own country where he was best known, serving instead through recitals and recordings as an ambassador to the rest of the world of Bach, Beethoven, Brahms and other cornerstones of German musical culture. Often acclaimed as the finest of all Death and the Maidens, this 1936 recording (with G�sta Andreasson, Karl Doktor and Adolf's younger brother Hermann) still overwhelms with its ideal blend of intense musicality and innate spirituality in which everything just sounds so "right." Every detail is heartfelt and impresses with its utter sincerity while preserving the musical continuity, never wresting attention from the music itself – technique as the servant of art. Phrasing, transitions, balances and inflection are smooth yet vividly characterized. All four players seem a single, perfectly-attuned instrument that exemplifies the old saying that a good quartet plays together while a great quartet breathes together.

And so many others � While the vintage Busch set a daunting, towering standard, among the more modern recordings I've heard (thank you, Spotify!) I can recommend: Hollywood String Quartet (1956, Capitol – mono, but exceptionally clear and nuanced), Juilliard Quartet (1960, RCA – edgy precision – and a great cover!), Italian Quartet (1965, Philips), Alban Berg Quartet (1985, EMI – dark but strong), Prague Quartet (1987, Denon – really heartfelt), Emerson String Quartet (1988, DG – assertive), Tokyo Quartet (1989, RCA – beautiful string tone), Kodaly Quartet (1992, Naxos – slow and expressive), Hagen Quartet (1992, DG – four siblings – vibrant finale), Belcea Quartet (2000, EMI), Jerusalem Quartet (2008, Harmonia Mundi), and Artemis Quartet (2009, Virgin – personal and quirky yet intriguing should others begin to sound too familiar).

|

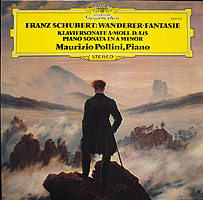

As inspiration for yet a third instrumental masterwork  Schubert turned to another early song – his 1816 "Der Wanderer" ("The Wanderer"). The poem by Georg Philipp Schmidt von L�beck is set over ominous triplets and presents a joyless stranger searching for happiness that eludes him everywhere he turns. Finally, a ghostly whisper provides an ominous answer that foretells eternal gloom – happiness is wherever he is not! Schubert's 1822 "Wanderer" Fantasy for piano is one of the earliest manifestations of the epic outlook that infused much of his later work. Despite being titled a fantasy and played through continuously, its form suggests a sonata, with sections corresponding to the four traditional movements. As with the Trout and Maiden the song's melody directly feeds the slow section. Yet Schubert also uses its accompaniment to serve as a unifying motif – the disarmingly simple rhythm of a quarter and two eighth notes that also infused the Death and the Maiden Quartet (but modified to a dotted quarter, eighth and quarter for the triple rhythm of the scherzo) appears throughout the 22-minute work, from the energized nobility of the opening to the resolute power of the concluding fugue, as if to suggest that the composer was searching everywhere throughout the world of musical possibilities for the comfort and contentment of an elusive home and, in the process, crafted a massive set of variations. And here, too, it seems fair to infer his psyche both from his choice of the song and the way he developed it into a new work. It is believed to have been written just as Schubert realized he was stricken with syphilis; forced to confront mortality at such a tender age, the composer understandably was shaken but deepened his outlook into visionary realms (as he did in his symphonic writing with the impassioned "Unfinished" Symphony which he began – and abandoned – at about the same time).

Schubert turned to another early song – his 1816 "Der Wanderer" ("The Wanderer"). The poem by Georg Philipp Schmidt von L�beck is set over ominous triplets and presents a joyless stranger searching for happiness that eludes him everywhere he turns. Finally, a ghostly whisper provides an ominous answer that foretells eternal gloom – happiness is wherever he is not! Schubert's 1822 "Wanderer" Fantasy for piano is one of the earliest manifestations of the epic outlook that infused much of his later work. Despite being titled a fantasy and played through continuously, its form suggests a sonata, with sections corresponding to the four traditional movements. As with the Trout and Maiden the song's melody directly feeds the slow section. Yet Schubert also uses its accompaniment to serve as a unifying motif – the disarmingly simple rhythm of a quarter and two eighth notes that also infused the Death and the Maiden Quartet (but modified to a dotted quarter, eighth and quarter for the triple rhythm of the scherzo) appears throughout the 22-minute work, from the energized nobility of the opening to the resolute power of the concluding fugue, as if to suggest that the composer was searching everywhere throughout the world of musical possibilities for the comfort and contentment of an elusive home and, in the process, crafted a massive set of variations. And here, too, it seems fair to infer his psyche both from his choice of the song and the way he developed it into a new work. It is believed to have been written just as Schubert realized he was stricken with syphilis; forced to confront mortality at such a tender age, the composer understandably was shaken but deepened his outlook into visionary realms (as he did in his symphonic writing with the impassioned "Unfinished" Symphony which he began – and abandoned – at about the same time).

Critics have admired the Wanderer Fantasy  for its dense textures that manage to respect the essential percussive nature of the piano while at the same time stretching it with tremelos, doublings, repeated notes and many-voiced chords to suggest the resources and density of an orchestra. Nearly alone among Schubert's output, it's one of the few overtly virtuostic works he wrote; reportedly, Schubert became frustrated trying to play it. Its tightly-organized, cyclical structure formalizes the improvisational nature of prior fantasias of Mozart and Beethoven. Its innovations were models for Franz Liszt, who seized upon a similar structure and treatment of the piano for his own influential 1854 Sonata in B Minor (but who uncharacteristically simplified the original writing when he adapted Schubert's solo Wanderer Fantasy for piano and orchestra in an effective arrangement reminiscent of his own two concertos).

for its dense textures that manage to respect the essential percussive nature of the piano while at the same time stretching it with tremelos, doublings, repeated notes and many-voiced chords to suggest the resources and density of an orchestra. Nearly alone among Schubert's output, it's one of the few overtly virtuostic works he wrote; reportedly, Schubert became frustrated trying to play it. Its tightly-organized, cyclical structure formalizes the improvisational nature of prior fantasias of Mozart and Beethoven. Its innovations were models for Franz Liszt, who seized upon a similar structure and treatment of the piano for his own influential 1854 Sonata in B Minor (but who uncharacteristically simplified the original writing when he adapted Schubert's solo Wanderer Fantasy for piano and orchestra in an effective arrangement reminiscent of his own two concertos).

Recordings of the Wanderer Fantasy present a wide variety of approaches, as would be expected with solo artists, who can craft individualized readings more readily than ensembles: Alfred Brendel (Turnabout or Phillips) tends to clarify the structure, Arthur Rubinstein (RCA) is rather formal, Clifford Curzon (Decca) tender, Maurizio Pollini (DG) taut and clear, Svatislav Richter (EMI) full-blooded and Murray Perahia (Sony) rich and probing. One of the earliest (1934) recordings, by Edwin Fischer (Pearl and other CDs), provides an especially inspired blend of drama and poetry.

![]() Schubert's derivative works are far more popular than the original songs that inspired them. While few would deny an author the right to clone his own work (so long as he didn't pass off the result as a wholly new piece), perhaps there's a further consideration here.

Schubert's derivative works are far more popular than the original songs that inspired them. While few would deny an author the right to clone his own work (so long as he didn't pass off the result as a wholly new piece), perhaps there's a further consideration here.

It's sad enough that visionary composers can be sued nowadays for their creative use of existing music. But judicial interpretation of current U.S. copyright law goes further by imposing liability for infringement even upon coincidental similarity. With all the music out there (and there's quite a lot – BMI alone claims 12 million compositions in its catalog) composers nowadays are placed at constant risk, a state of jeopardy that would be partially relieved by limiting our domestic copyright protection to a reasonable period (as the Constitution requires) rather than constantly lengthening it essentially to perpetuity, by extending the public domain to works in which authors apparently have lost interest and, above all else, by expanding our legal notions of originality to encourage resourceful adaptations of our shared culture. (For more on this troubling concern, please see "Your Riff Or Mine", my article from the October 2005 issue of IP Law & Business.) Fortunately, more enlightened views prevailed when Schubert expanded his own songs into ageless masterworks.

It's sad enough that visionary composers can be sued nowadays for their creative use of existing music. But judicial interpretation of current U.S. copyright law goes further by imposing liability for infringement even upon coincidental similarity. With all the music out there (and there's quite a lot – BMI alone claims 12 million compositions in its catalog) composers nowadays are placed at constant risk, a state of jeopardy that would be partially relieved by limiting our domestic copyright protection to a reasonable period (as the Constitution requires) rather than constantly lengthening it essentially to perpetuity, by extending the public domain to works in which authors apparently have lost interest and, above all else, by expanding our legal notions of originality to encourage resourceful adaptations of our shared culture. (For more on this troubling concern, please see "Your Riff Or Mine", my article from the October 2005 issue of IP Law & Business.) Fortunately, more enlightened views prevailed when Schubert expanded his own songs into ageless masterworks.

![]() While I'll take the credit (and accept the blame) for the musical judgments in this article, I gratefully acknowledge the following resources for the quotations, citations and factual information:

While I'll take the credit (and accept the blame) for the musical judgments in this article, I gratefully acknowledge the following resources for the quotations, citations and factual information:

- Affelder, Paul: notes to the Vienna Konzerthaus Quartet "Maiden" LP (Westminster WL 5052, 1950)

- Ashley, Joan: notes to the Cleveland/Brendel "Trout" LP (Philips 9500 442, 1977)

- Brown, Maurice: "Franz Schubert" article in Eric Blom, ed.: Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians (St. Martin's Press, 1954)

- Clay, Priam: notes to the Tokyo Quartet "Maiden" LP (Vox Cum Laude VCL 9004, 1982)

- Donat, Misha: notes to the Takasz Quartet "Maiden" CD (Hyperion CDA 67585, 2006)

- Finkelstein, Stanley: notes to the Serkin, et al. "Trout" LP (Vanguard VSD-71145, 1965)

- Forman, Frank: Acoustic Chamber Music Sets (1899-1926): A Discography (Journal of the Association for Recorded Sound 31/1, 31/2 and 32/1, 2000-1)

- Golding, Robin: notes to the Melos Ensemble "Trout" LP (Angel S-36641, 1967)

- Griffel, L. Michael: "Der Tod und die Forelle: New Thoughts on Schubert's Quintet" (Current Musicology 79-80, pp. 55-66, 2005)

- Grove, George: "Franz Schubert" article in J. A. Fuller Maitland, ed.: Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Macmillan, 1908)

- Holocek, Jaroslav: notes to the Prague String Quartet "Maiden" LP (Supraphon 1111 1937, 1979)

- Hussey, Dyneley: notes to the Vienna Octet/Curzon "Trout" LP (Decca LXT-5433, 1957)

- Krellman, Hanspeter: notes to the Beaux Arts Trio/Rhodes "Trout" LP (Philips 9500 071, 1976)

- Lang, Paul Henry: Music in Western Civilization (Norton, 1941)

- Lyons, James: notes to the Hungarian Quartet "Maiden" LP (Chamber Music Society CM-17)

- Mann, William: "Franz Schubert" article in Alex Robertson, ed., Chamber Music (Penguin, 1957)

- Marcus, Michael: notes to the Aeolian String Quartet "Maiden" LP (World Record Club CM 9

- Matthews, David and Donald Mitchell: notes to the Tate/English Chamber Orchestra CD of Mahler's "Maiden" orchestration (EMI CDC C 7 47354 2, 1986)

- Mila, Massimo: notes to the Schnabel/Pro Arte "Trout" LP (Angel Great Recordings of the Century COLH 40, 1958)

- Myers, Paul: notes to the Smetana Quartet/Paneka "Trout" (Epic Crossroads 22 16 0030, 1977)

- Porter, Cecelia H.: notes to the Juilliard String Quartet "Maiden" LP (CBS 76827, 1981)

- Potter, Tully: notes to the "Capet String Quartet Play Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven" CD (Biddulph LAB 097, 1995)

- Rayment, Malcolm: notes to the Amadeus/Menuhin "Trout" LP (Angel S-35777, 1959)

- Reed, John: notes to the Vienna Octet/Curzon reissue "Trout" LP (London 417 439, 1987)

- Rich, Alan: notes to the Guarneri Quartet "Maiden" LP (RCA ARL-1934, 1976)

- Schauffler, Robert: quoted in David W. Eagle: notes to the Prague Quartet "Maiden" LP (Pro Arte PLA-1036, 1981)

- Simon, Henry W.: noes to the Juilliard String Quartet "Maiden" LP (RCA LSC-2378, 1960)

- Standage, Jennifer: notes to the Quartetto Italiano "Maiden" LP (Philips PHS 900-139 (1976)

- Steinberg, Michael: notes to the Fine Arts Quartet "Maiden" LP (Concert-Disc CS-212, 1961)

- Townsend, Douglas: notes to the Novak Quartet "Maiden" LP (Musical Heritage Society MHS 1202, 1976)

- Ulrich, Homer: Chamber Music (Columbia University Press, 1966)

- Winter, Robert: "Franz Schubert" article in Stanley Sadie, ed.: New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Macmillan, 2001)

And finally, the scores of all the compositions mentioned in this article, including the Schubert songs, the "Trout" Quintet, the "Death and the Maiden" Quartet and the "Wanderer" Fantasy, are available for free downloads from the fabulous Petrucci Music Library.

![]()

Copyright 2017 by Peter Gutmann

copyright © 1998–2017 by Peter Gutmann. All rights reserved.